Microcampus 2024

Microcampus 2024 Book

Microcampus 2024 Packing List

Microcampus 2024 Itinerary

China’s Silk Roads and the Significance of Gansu Province

For centuries Gansu was the vital corridor between China and Central Asia: there passed almost 1600-kilometre section of the Silk Road. The province was considered the “gold sector” of that international route. As proof, you will see numerous ancient monuments scattered along the entire Silk Road – temples, monasteries, pagodas, towers, and ancient palaces. Besides, the province has a considerable part of the Great Wall of China, whose ruins can impress you with their sizes.

The territory of the modern province of Gansu was conquered and developed before the Christian era. Gansu province was first mentioned in the sources of the imperial dynasty Northern Song (960-1127) when the imperial military department on Gansu affairs was established in Ganzhou (now Zhangye). In the time of the Mongolian Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), the region was officially annexed to the territory of Gansu province. It was created by merging Qingyuan, Lingao, and Feng.

The region is well-known for its traditions of horse breeding (the first farms appeared during the rule of Wu of Han in 100 BC). From there horses started spreading all over China; the battle horses from Gansu were the backbone of the military divisions of the ancient Chinese army.

The region has repeatedly changed its names: Ganzhou (Cao Wei – 220-265, Tang dynasty – 618-907), Suzhou (the old name of the modern city of Jiuquan). In antiquity, the area was also named Lunsi or Luniu marking the region’s geographical position in the western part of the Lunshan mountains.

Standing on the Silk Road made the territory multinational. As a result, various religions have settled there: Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, Confucianism, and Taoism. The province is populated by Tibetans, Hui people, Uyghur people, and Mongols.

Cities Along the Silk Road in Gansu Province

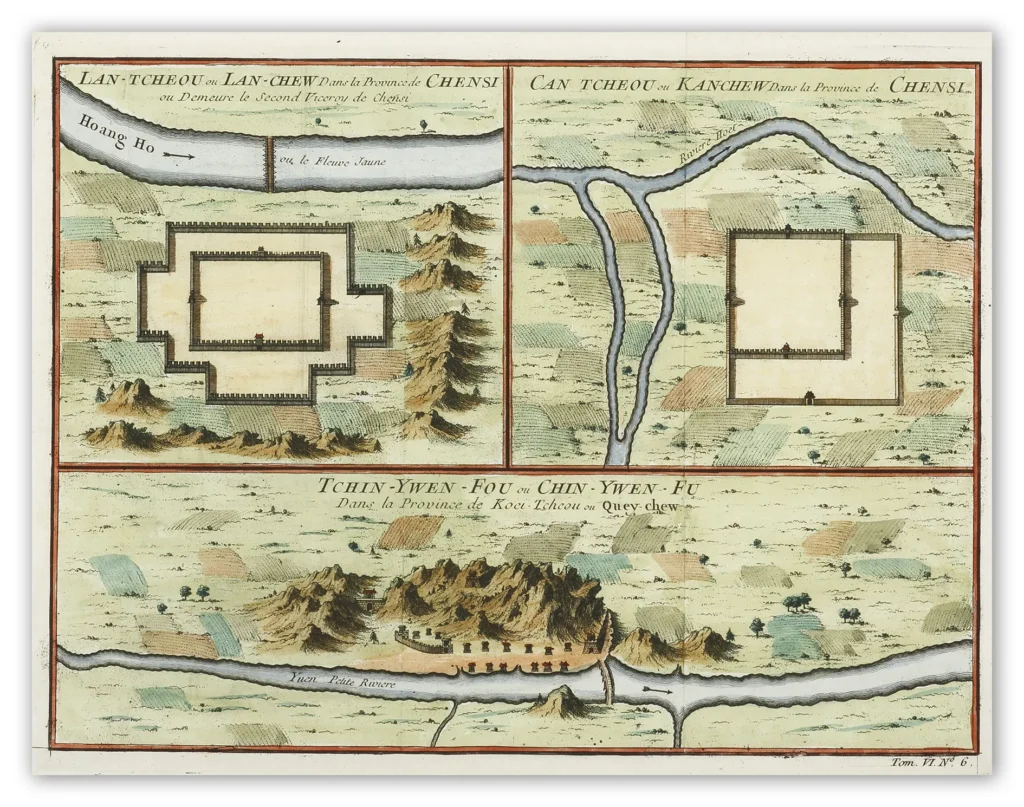

Lanzhou

Originally in the territory of the Xi (Western) Qiang peoples, Lanzhou became part of the territory of Qin in the 6th century BCE. Under the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), it became the seat of Jincheng xian (county) in 81 BCE and later of Jincheng jun (commandery); the county was renamed Yunwu. In the 4th century it was briefly the capital of the independent state of Qian (Former) Liang. The Bei (Northern) Wei dynasty (386–534/535) reestablished Jincheng commandery and renamed the county Zicheng.

Under the Sui dynasty (581–618) the city became the seat of Lanzhou prefecture for the first time, retaining this name under the Tang dynasty (618–907). In 763 the area was overrun by the Tibetans, and it was then recovered by the Tang in 843. Later it fell into the hands of the Xi (Western) Xia (Tangut) dynasty (which flourished in Ningxia from 1038 to 1227) and was subsequently recovered by the Song dynasty (960–1127) in 1041, who reestablished the name Lanzhou. After 1127 it fell into the hands of the Jin (Juchen) dynasty (1115–1234), and after 1235 it came into the possession of the Mongols. Under the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) the prefecture was demoted to the status of a county and placed under the administration of Lintao superior prefecture, but in 1477 Lanzhou was reestablished as a political unit. In 1739 the seat of Lintao was transferred to Lanzhou, which was later made a superior prefecture also called Lanzhou. When Gansu became a separate province in 1666, Lanzhou became its capital.

The Gansu Provincial Museum

The city was badly damaged during the rising of Gansu Muslims in 1864–75; in the 1920s and ’30s it became a centre of Soviet influence in northwestern China. During the Sino-Japanese War (1937–45) Lanzhou, linked with Xi’an by highway in 1935, became the terminus of the 2,000-mile (3,200-km) Chinese-Soviet highway, used as a route for Soviet supplies destined for the Xi’an area. This highway remained the chief traffic artery of northwestern China until the completion of a railway from Lanzhou to Ürümqi in the Uygur Autonomous Region of Xinjiang. During the war Lanzhou was heavily bombed by the Japanese.

Lanzhou Pulled Noodles

It is said that Lanzhou, China has three local treasures. As the saying goes, “auspicious gourd and beef noodles, and sheepskin raft like warship”. One of the oldest beef noodle soups is the Lanzhou hand-pulled noodle or Lanzhou lamian (Chinese: 兰州拉面) in Mandarin, which was originated by the Hui people of northwest China during the Tang dynasty.[1][2] Though there is some debate about when Lanzhou hand-pulled noodles originated, the recipe is named after the major city in Gansu Province, Lanzhou City, which stretches to the Yellow River and was a stop on the ancient Silk Road. The Hui Muslim population or Hui People developed a variation of beef noodle soup noodle that is compatible with the Muslim diet with easy to prepare ingredients.[3] There are numerous beef noodle soups available in China, with a wider variety in the west than the east.

Zhangye

The city was formerly also known as Ganzhou, named after the sweet waters (Chinese: 甘泉; pinyin: Gānquán) of its oasis. An alternative theory states that “Gan” was from the Ganjun Hill (绀峻山) near the city. The name of province came from a contraction of Ganzhou and Suzhou (modern Jiuquan). The name appears in Marco Polo‘s Travels under the name Campichu.[3]

Zhangye Commandery was established by Western Han in 111 BC, with the seat at the site of modern Wuwei, Gansu. Etymology of Zhangye is unclear. A popular theory interprets the name Zhangye as “Extending Arm”, excerpted from a phrase “to extend the arm of the country through to the Western Realm” (张国臂掖,以通西域) documented in Han Shu.[4]

Zhangye lies in the centre of the Hexi Corridor. The area is on the frontier of China proper, protecting it from the nomads of the northwest and permitting its armies access to the Tarim Basin. During the Western Han dynasty, Han armies were often engaged against the Xiongnu in this area. It was also an important outpost on the Silk Road.[citation needed] Before being over-run by the Mongols, it was dominated by the Western Xia dynasty, and before by the Uyghurs from at least the early 10th century. Its relation to the larger Uyghur state of Qocho is obscure, but it may have been a vassal.[5]

The Yuan dynasty founding emperor Kublai is said to have been born in the Dafo Temple, Zhangye, now the site of the longest wooden reclining Buddha in China.[citation needed] Marco Polo‘s journal states that he spent a year in the town during his journey to China.[3]

The pine forests of the Babao Mountains (part of the Qilian range) formerly regulated the flow of the Ruo or Hei Shui, Ganzhou’s primary river. By ensuring that the melt-waters lasted throughout the summer, they avoided both early flood and later drought for the valley’s farmers. Despite recommendations that they should thus be protected in perpetuity, a Qing dynasty imperial official in charge of erecting the poles for China’s telegraph network ordered them cleared in the 1880s. Almost immediately, the region became prone to flooding in the summer and draught in the autumn, arousing local resentment.[6]

Christian missionaries arrived in 1879, after Suzhou (modern-day Jiuquan) was found to be too hostile for their settlement.[7]

Jiayuguan

Jiayuguan Pass used to be the starting point of the ancient Great Wall built during Ming Dynasty (1368 – 1644). It was the most important military defensive project guarding the far northwestern area of China because of its strategic location at the narrowest point of the western section of the Hexi Corridor which had been the vital defensive frontier since Han Dynasty (BC 202—220). After the Jiayuguan Pass was constructed, the army of Ming Dynasty used it to protect inner China from the invasion of nomadic groups. At the same time, the Jiayuguan Pass had also played as a key waypoint of the ancient Silk Road. Foreign travelers and traders came from Europe, Middle Asia, and entered the inner land of China. While commodities of China also were transported to Middle Asia and Europe from this pass. Along with the foreign trade, a cultural exchange of religion, art and custom also had been brought.

Jiayu Pass was built in the Ming Dynasty (1368 – 1644) under the supervision of Feng Sheng, a founding general of the Ming Dynasty. When first completed, there were only ramparts surrounding the barracks. After 168 years of enhancements, the pass assumed its present appearance.

Covering an area of 33,529 square meters (40,100 square yards), Jiayuguan Pass of Great Wall has a complex and integrated defensive system: an inner city, the central area with many buildings, an outer city, and finally a moat. You can also find common military facilities such as arrow towers, turrets, and cannons along the wall.

Jiayu Pass was also a vital traffic fort along the Silk Road, the world’s oldest trading route, connecting China, Central Asia and Europe.

Dunhuang

The city of Dunhuang, in north-west China, is situated at a point of vital strategic and logistical importance, on a crossroads of two major trade routes within the Silk Road network. Lying in an oasis at the edge of the Taklamakan Desert, Dunhuang was one of the first trading cities encountered by merchants arriving in China from the west. It was also an ancient site of Buddhist religious activity, and was a popular destination for pilgrims, as well as acting as a garrison town protecting the region. The remarkable Mogao Caves, a collection of nearly 500 caves in the cliffs to the south of the city, contain the largest depositary of historic documents along the Silk Roads and bear witness to the cultural, religious, social and commercial activity that took place in Dunhuang across the first millennium. The city changed hands many times over its long history, but remained a vibrant hub of exchange until the 11th century, after which its role in Silk Road trade began to decline.

The Silk Road routes from China to the west passed to the north and south of the Taklamakan Desert, and Dunhuang lay on the junction where these two routes came together. Additionally, the city lies near the western edge of the Gobi Desert, and north of the Mingsha Sand Dunes (whose name means ‘gurgling sand’, a reference to the noise of the wind over the dunes), making Dunhuang a vital resting point for merchants and pilgrims travelling through the region from all directions. As such, Dunhuang played a key role in the passage of Silk Road trade to and from China, and over the course of the first millennium AD, was one of the most important cities to grow up on these routes. Dunhuang initially acted as a garrison town protecting the region and its trade routes, and a commandery was established there in the 2nd century BC by the Chinese Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD). A number of ancient passes, such as the Yü Guan or “Jade Gate” and the Yang Guan, or “Southern Gate”, illustrate the strategic importance of the city and its position on what amounted to a medieval highway across the deserts.

The history of this ancient Silk Road city is reflected in the Mogao Caves, also known as the Qianfodong (the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas), an astonishing collection of 492 caves that were dug into the cliffs just south of the city. The first caves were founded in 366 AD by Buddhist monks, and distinguished Dunhuang as a centre for Buddhist learning, drawing large numbers of pilgrims to the city. Monks and pilgrims often travelled via the Silk Roads, and indeed a number of religions, including Buddhism, spread into areas around the trading routes in this way. There were some 15 Buddhist monasteries in the city by the 10th century, and the latest caves were carved sometime in the 13th or 14th century. The city also lay on the pilgrim route from Tibet to the sacred Mount Wutai. The caves were painted with Buddhist imagery, and their construction would have been an intensely religious process, involving prayers, incense and ritual fasting. The earliest wall paintings date back to the 5th century AD, with the older paintings showing scenes from the Buddha’s life, whilst those built after 600 AD depict scenes from Buddhist texts.

The Mogao Caves illustrate not only the religious importance of Dunhuang however, but also its significance as a centre of cultural and commercial exchange. One of the caves, known as the ‘library cave’, contains as many as 40,000 scrolls, a depositary of documents that is of enormous value in understanding the cultural diversity of this Silk Road city. The earliest text is dated to 405 AD, whilst the latest dates to 1002 AD. The arrangement of documents in this library cave suggests that they were deliberately stored there, and it seems likely that the local monasteries used the cave as a store room. They provide a picture of Dunhuang as a vibrant hub of Silk Road trade, and give an indication of the range of goods that were exchanged in the city. According to these documents, a large number of imports arrived from as far away as north-east Europe. Interestingly, the scrolls that mention merchant caravans are usually written in Sogdian, Uighur, or Turco-Sogdian, indicating that they were produced by the foreign traders in the city. The range of imported goods included brocade and silk from Persia, metal-ware, fragrances, incense and a variety of precious stones, such as lapis lazuli (from north eastern Afghanistan), agate (from India), amber (from north east Europe), coral (from the ocean) and pearl (usually from Sri Lanka). Dunhuang was not simply a recipient of trade however, and had a very active export market too. The scrolls refer to a large number of goods that were produced in city and its surrounding regions and sold to merchants, including silks of many varieties, cotton, wool, fur, tea, ceramics, medicine, fragrances, jade, camels, sheep, dye, dried fruits, tools, and embroidery. This unique view of the imports and exports from the markets of Dunhuang illustrates the vibrancy of Silk Road trade along the routes into western China.

Additionally, although they were collected and stored by Buddhist monks, these scrolls shed light on the many different religions and languages in Dunhuang across the first millennium. In addition to Buddhist texts, Zoroastrian, Manichee, Eastern Christian, Daoist, and Jewish documents can be found in this collection, suggesting that communities of many different religions lived side by side in the city. Although the majority of the scrolls are in Chinese and Tibetan, there are also texts in Sanskrit, Khotanese, Uighur, and Sogdian, as well as one Hebrew prayer, folded and carried in a small purse and probably worn as a talisman by a traveller or merchant. These were all languages of the traders who travelled to Dunhuang from the surrounding regions, and their storage in the Mogao Caves suggests that these foreign trading communities were a vital part of the city’s social structure and of the wider, cosmopolitan community.

Crafts and skills also moved along the Silk Roads as traders and craftsmen met and exchanged notes, and a small number of scrolls in the Mogao Caves illustrate the use of woodblock printing in Dunhuang, a technique that originated in China in the early 8th century. The most famous text in the library cave, the Diamond Sutra, which dates to 868 AD, was made using this technique and is the first complete printed book in the world. Woodblock printing would later spread across Asia, as traders passed on knowledge and ideas that they had acquired whilst travelling the Silk Roads.

Microcampus 2024 Survey

Share Your Thoughts on the Microcampus 2024 Trip