LAND-BASED EMPIRES

Empires Expand

The period 1450 to 1750 saw the rise of massive land-based empires across Eurasia. Although the expansion of these empires bore many similarities, each of them also adapted and responded to the peculiar geographic, cultural, and ethnic realities of their regions.

All empires in this period benefited from the use of gunpowder. The fall of Constantinople in 1453, a result of new siege cannons that brought down the city’s fortifications, demonstrated the effectiveness of firearms and artillery in a very dramatic fashion. Small states did not have the resources to produce these weapons or to equip their soldiers with them. Consequently, empires, with their access to vast resources, had the advantage and were able to marshal large professional armies equipped with firearms which they used to quickly project power across the continent.

But rapid expansion came with its own set of challenges. Empires found themselves presiding over vastly diverse empires and had to navigate deep ethnic and religious divisions. In some cases, such as China’s Qing Dynasty, the empire was ruled by an ethnic minority group who had invaded from outside. In other cases, such as the Mughals, the ruling elites were Muslim invaders ruling over a Hindu majority. In all empires, belief systems played a role in legitimizing power, a reality that created tensions and rivalries between empires.

Manchu Empire

Near the end of the previous period (1200-1450), the Ming overthrew Mongol rule and set up a new Chinese dynasty. They established the previous bureaucratic/Confucian political system and sought commercial and tributary contacts with the states in Asia and the Indian Ocean. The Ming sponsored voyages, such as those led by Admiral Zheng He, to restore former Chinese preeminence in the world. In the 1430s these voyages were stopped. The Chinese government decided to devote its resources to purifying its empire and protecting them from further nomadic invasions.

By the 1600s the Ming dynasty had grown weak and corrupt. As they declined, the Manchu people across the Great Wall were expanding, unifying a strong state and borrowing Chinese bureaucratic institutions. In 1644 the Manchus entered China and easily drove all the way to Beijing where they defeated the weakened Ming and established their own rule over China, the Qing Dynasty. The Qing Dynasty would be characterized by a problem some other land-based empires had in this time period—a minority ruling a different ethnic or religious majority. To bridge the gap between themselves and the ethnic Han Chinese, the Manchus implemented the civil service Confucian bureaucracy. Chinese were allowed to rise in the political system, and Qing Emperors adopted the Chinese title Son of Heaven.

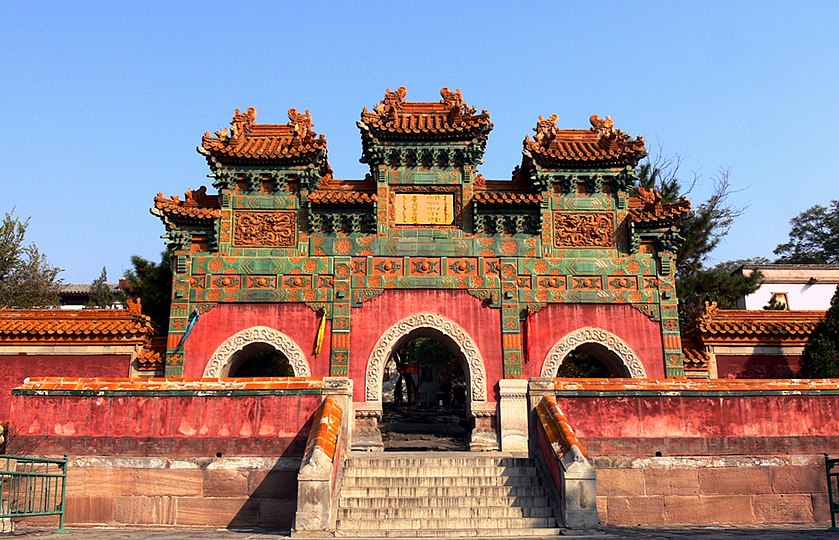

The Manchu emperors began the practice of publically performing Confucian rituals to gain political legitimization from the Chinese. For example, each year the Emperor would plow the first furrow of ground in front of the Temple of Agriculture (see above). This symbolic gesture was to ensure a good harvest. Most everything the emperor did was choreographed with Confucian rituals. The Manchu emperors continued these rituals. They also kept the classical Confucian texts as the basis of the civil service examination system. The Manchus utilized the nobles of conquered areas to help them administrate and control their growing empire. Buddhists and Muslim leaders, as well as Mongol aristocrats, were given positions in the Qing.

They respected local traditions by exempting Buddhist monks and monasteries from state labor service and taxes. They respected Mongol traditions by not allowing the Chinese to migrate into Mongol territory and dilute Mongol culture. Indeed, the Qing respected Tibetan, Mongol, and Buddhist culture, a practice that eased the expansion of the Qing Empire into new areas.

The Manchus outlined what is today the general borders of China, and by respecting the cultures of minorities they preserved a sense of identity for many of these groups and endowed them with an enduring sense of autonomy (consider Tibet, for example). Despite the fact that ethnic Chinese were allowed to rise in the bureaucracy, the Manchus preserved the highest positions in the government for themselves. They maintained their cultural integrity by banning marriage between Manchus and Chinese. Han Chinese were forbidden to move into the Manchu homeland. They forced the Chinese to forgo the Ming-style robes in favor of Manchu garments and ordered the Chinese to adopt the Manchu hairstyle of shaving the front of the head and braiding the long hair in the back into a queue.

Much of what the Manchu accomplished resembled previous Chinese dynasties. They centralized rule through a bureaucracy. They expanded militarily far into central Asia and established tributary relations with Vietnam, and Burma. Korea and Nepal. They focused China’s economic strength more on the practice of agriculture than they did commerce; the city of Canton in the south of China was the only location where trade with Europe was allowed. As new crops were transplanted from the New World, the Qing experienced a large population growth commensurate with their territorial growth. In some areas, silk production exceeded rice production and consumed all the surplus labor of peasant families.

The Mughals were another Turkish group of people. They claimed descent from Genghis Khan (Mughal is a Persian term for Mongol). Like the Ottomans, they relied on a military elite armed with firearms and created a strong centralized empire organized with a bureaucracy. They expanded into the south and unified much of the Indian subcontinent where they ruled an empire comprised mainly of Hindus. Thus the rulers and the ruled were divided along religious lines. The most famous Mughal leader, Akbar, attempted to bridge this divide through a policy of tolerance. He married Hindu princesses but did not require them to convert. Hindus were given positions in the government. He invited Christian, Hindu, and Muslim scholars to peaceful open debates about the merits of their religions. He removed the religious tax on non-Muslims. Akbar created his own syncretic religion called “the divine faith” which drew on Islamic, Hindu, and Zoroastrian beliefs.

This religion pointed to the emperor as the leader of all faiths in the empire. All this drew the anger of conservative Muslim teachers. Subsequent Mughal leaders fell under the sway of these conservatives and Akbar’s policy of toleration was later abandoned. Hindu temples were destroyed. Religious tension reemerged as a central problem of the Empire.

During his reign, Akbar significantly reformed the Mughal bureaucracy. Previously, the Mughal emperors collected taxes by relying upon a decentralized network of local administrators called zamindars. Acting as local aristocratic landlords, they collected taxes from peasants and sent a set quota to the state. But much of this revenue never made it to the emperor. As profits from the Indian Ocean pepper trade increased, Akbar monetized the tax system (required taxes paid in currency rather than in kind) and required the peasants to sell their grain in market towns and ports for cash where oversight of taxation could be more controlled. Having been bypassed in the taxation process, the role of the zamindars as tax-collecting landlords decreased; political control was also centralized. State profits poured directly into the government’s purse. This windfall of revenue was used to fund military expeditions and embellish the imperial courts. With the decreased role of the zamindars, Akbar began the process of political centralization.

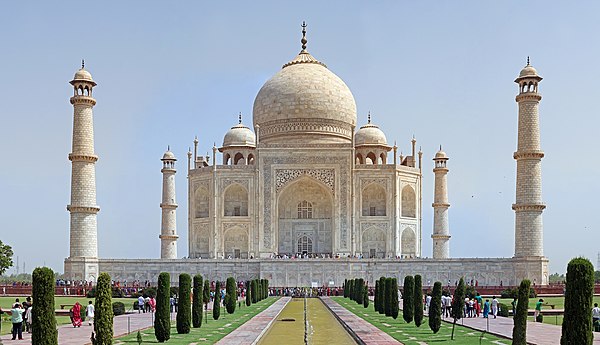

The most important beautification of the imperial courts was by emperor Shah Jahan. Jahan ruled during the commercial boom of the Mughal Empire and was flush with silver from the New World used to purchase tons of Indian pepper. He constructed the Taj Mahal in memory of his favorite wife. This architectural wonder of the world was a monument to the enormous wealth of the Mughal state and displayed the power of the emperor.

During the Mughal empire, the price of spices declined. To maintain their profits, joint-stock companies such as the British East India Company and the Dutch VOC encouraged Mughal leaders to supplement pepper exports with cotton textiles. Cotton, which was softer than many fabrics and could be dyed and printed with elaborate patterns, became an extremely popular fad in Europe. To meet this demand, the Mughal government forced a vast number of peasants to work cotton fields and textile operations. As in Russia, state mandates and incentives led to the mass mobilization of peasants to aid state objectives.

The Ottomans began as Turkish nomadic people, comprised of aggressive and warlike tribes who raided agricultural people. After the Mongols crushed the Seljuks, the Ottomans had room to emerge as a powerful empire.

The Ottoman conquests expanded into the Byzantine Empire, a process that culminated in the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Many former Byzantines in Anatolia converted to Islam. In the Balkans, many remained Christian. Orthodox churches were allowed to remain. Despite their territorial conflicts with Christian Europe, most Christians in the Empire were permitted to practice their faith. Jewish, Christian and other minorities could maintain autonomous communities with their own civil laws and customs. The Ottomans recruited many non-Muslims into their elite and relied on their skills for trade and craftsmanship. In fact, a Hungarian Christian cast the cannons that allowed Mehmed II to conquer the Christian city of Constantinople.

Originally military leaders were called the ghazis (elite Muslim warriors or champions: Mehmed II, who took the city of Constantinople, used this as one of his titles). Later the military grew into a powerful cavalry. As horses need grazing land, the military machine of the Ottoman Empire was based on constant expansion. The wealth from new land grants was used to support the military elites. Thus the Ottoman Empire was strong as long as it was expanding.

The practice of Devshirme (collecting, or gathering) became important to the Ottoman state. Large conquered Christian communities were required to hand over a quota of young boys. They were taught Turkish and many of them converted to Islam. Many of these boys became members of the elite Janissaries. These troops came from non-Muslim homes, were raised by the state, and depended on the Ottoman state rather than their families. This made them loyal warriors. The Janissaries were also the primary users of firearms, and gunpowder became an essential feature of Ottoman expansion.

Ottoman Empire grew second only to Ming China in Eurasia. It was a state based on expansion, and thus military leaders were the elites (compare with China). The growth of the Ottoman Empire was always seen as a threat to Western Christian Europe. Ottomans unsuccessfully laid siege to Vienna twice. As the Ottoman Empire expanded into Persia, they clashed with the Safavid Empire, the Shi’a heirs of the Persian Empire. This clash came to be an epic struggle between the Sunni and Shi’a forms of Islam. The Ottomans gained a decisive victory over the Safavids at the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514, an event that stopped the expansion of Shi’a Islam and regulated it largely to the area of present-day Iran.

Russian Empire

During this era the Russians broke free from Mongol domination and began a period of territorial expansion and government reform. They embarked on an aggressive program of westernization in order to leap forward and make up for their backwardness vis-à-vis the West. The forced imposition of European culture on the aristocracy of Russia created a wide cultural difference between the upper class and the peasants, a situation that only exacerbated the social tensions between serfs and nobles that were already present.

The first significant leader in this process was Ivan III, also known as Ivan the Great. In a carefully calculated political move, Ivan married the niece of the last Byzantine Emperor and claimed continuity with imperial Rome and the Byzantine Empire. He proclaimed Moscow the “Third Rome” (Constantinople had been the “Second Rome) and exploited his close ties to the Orthodox Church to give legitimacy to his wars of territorial expansion. All in all, Ivan III increased the power of the central Russian government and drew more land under his control. But another Ivan, Ivan IV, would push these advancements to new levels.

Ivan IV (The Terrible) extend the Russian empire by defeating the Mongol stronghold city of Kazan. He motivated his soldiers by telling them they were marching as soldiers of Christ (the Mongols had converted to Islam). To commemorate this victory he commissions the building of St. Basil’s Cathedral, an architectural symbol of the union of church and state.

Ivan’s most important contribution to the development of Russia is how he dealt with the powerful class of Russia’s aristocrats, the Boyars. If you remember, aristocrats have always been a problem for kings and emperors trying to centralize rule over large territories. Ivan held deep suspicions toward the Russian boyars and simply had many of them killed. Others he forced from their homes to different areas, an action that weakened their class by stripping them from the local connections that had given them power and influence. Consequently, Tsars in Russia would become true autocrats, unhindered by the pressures and influence of aristocracies. For example, even the absolute monarchy of Louis XIV in France was partially limited by the will of the nobles. But in Russia titles of nobility could be conferred or withdrawn arbitrarily by the Tsar. Thus the Russian nobility was kept in subservience to the state and would never emerge as a counterforce to the monarch’s power. Their traditional power over local affairs was striped and the power of Russian Tsars would truly be absolute.

In no Tsar was this absolute power more obvious than in Peter the Great. As a young man, he took the first of several trips to Europe, where he studied shipbuilding and other western technologies, as well as governing styles and social customs. He returned to Russia convinced that the empire could only become powerful by imitating western successes, and he instituted a number of reforms that revolutionized it: The Petrine Reform.

- Military reform – He built the army by offering better pay and also drafted peasants for service as professional soldiers. He also created a navy by importing western engineers and craftsmen to build ships and shipyards, and other experts to teach naval tactics to recruits. He introduced modern firearms, and gunpowder did much to bring success to Russian military campaigns, as it did with so many other empires during this era.

- Building the infrastructure – The army was useless without roads and communications, so Peter organized peasants to work on roads and do another service for the government. He also borrowed the Mongol concept of postal service (the arrow messengers) to facilitate rapid communication across the empire

- Expansion of territory – Peter gained Russian territory along the Baltic Sea by defeating the powerful Swedish military. To gain warm weather ports, he tried to capture access to the Black Sea, but he was soundly defeated by the Ottomans who controlled the area. He pushed the empire far to the east in Siberia, reaching the Bering Strait across from Alaska.

- Reorganization of the bureaucracy and taxation – In order to pay for his improvements, the government had to have the ability to effectively tax its citizens. The bureaucracy had been controlled by the boyars, but Peter replaced them with merit-based employees by creating the Table of Ranks, eventually doing away with titles of nobility. In terms of taxation, Peter reformed the tax system. Instead of a tax on each household (which peasants would avoid by registering several families at a single household), Peter taxed on a per-person basis. Although very unpopular, it generated income to fund his ambitions.

- Relocation of the capital – Peter moved his court from Moscow to a new location on the Baltic Sea, his “Window on the West” that he called St. Petersburg. The city was built from scratch out of a swampy area, where it had a great harbor for the navy. Its architecture was European, of course. The move was intended to symbolically and literally break the hold that old Russian religious and cultural traditions had on the government.

Note that Peter’s reforms borrowed very selectively from Europe. He was not at all interested in Parliamentary governments or movements toward social reform. In this sense, he was much more concerned with the benefits of the Science Revolution than with the ideas of the Enlightenment philosophies; those things that directly benefited military progress and his own autocratic rule most interested him. Yet he did force European rules of etiquette and culture on his nobles. Beards, long considered a sign of religious piety and respect, had to be shaved off. He even forced the Russian upper class to practice European manners and appropriate French as the language of social life. In short, he did much to strengthen Russia into a modern imperial power but at the expense of fostering of a distinctly Russian identity. When Peter died, he left a transformed Russia, an empire that a later ruler, Catherine the Great, would further strengthen. But he also left behind a new dynamic in Russian society: the conflicting tendencies toward westernization mixed with the traditions of the Slavs to turn inward and preserve their own traditions.

To secure the new frontier settlements to the east that had grown since Ivan IV, Russian Czars encouraged peasants to migrate to Siberia. They were provided with incentives, such as grain, seeds, and farming tools. Many peasants sought to create a better and more independent life for themselves by moving east. Fur trappers push to the east as well to take advantage of the profitable trade in furs. For the most part, however, the eastern frontier was settled by peasant migrations who were encouraged by the Russian government.

Empires: Administration

Empires expanded and conquered new peoples around the world, but they often had difficulties incorporating culturally, ethnically, and religiously diverse subjects, and administrating widely dispersed territories. Agents of the European powers moved into existing trade networks around the world. In Africa and the greater Indian Ocean, nascent European empires consisted mainly of interconnected trading posts and enclaves. In the Americas, European empires moved more quickly to settlement and territorial control, responding to local demographic and commercial conditions. Moreover, the creation of European empires in the Americas quickly fostered a new Atlantic trade system that included the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Around the world, empires and states of varying sizes pursued strategies of centralization, including more efficient taxation systems that placed strains on peasant producers, sometimes prompting local rebellions. Rulers used public displays of art and architecture to legitimize state power. African states shared certain characteristics with larger Eurasian empires. Changes in African and global trading patterns strengthened some West and Central African states — especially on the coast; this led to the rise of new states and contributed to the decline of states on both the coast and in the interior.

An individual’s claim to have authority over other people is not something we humans take for granted. We need a reason to obey. Coercion and force have long been a part of political power, but we yield to them out of fear or for pragmatic reasons rather than our belief that they constitute legitimate reasons for our consent. A state has political legitimacy when subjects choose to recognize its authority because it has some intrinsic validating quality. Notions used by states to legitimize their rule in this period (1450-1750) are examples of important continuities of state-building we have seen since the River Valley Civilizations in Period I. Religion and art continued to be closely connected with the political power of states.

Some examples of religious ideas legitimizing states are:

- European notions of divine right. The divine right of kings is an important political ideology in Western Europe. It maintains that the king’s authority comes from God and, as such, the king is accountable only to God for his actions. Thus it supports the idea of absolute monarchy in which the monarch’s power is not checked by any earthly agent. In Roman Catholic countries it means that the king’s power must be endorsed by the pope, a tradition that goes back to Charlemagne’s coronation in the year 800 C.E. Here, for example, is an account of the coronation of Charlemagne:

On the most holy day of the nativity of the Lord when the king rose from praying at Mass before the tomb of blessed Peter the apostle, Pope Leo placed a crown on his head and all the Roman people cried out, “To Charles Augustus, crowned by God, great and peace-giving emperor of the Romans, life and victory.” And after the laudation he was adored by the pope in the manner of the ancient princes and, the title of Patrician being set aside, he was called emperor and Augustus. The ideology of the divine right of kings reached its highest expression during the reign of Louis XIV of France. As Louis was consolidating his control of France, his chief theologian, Jacque Bousset, wrote a work called Politics Drawn from the Words of Holy Scripture which justified the absolute monarchy King Louis was creating. “Monarchical authority comes from God,” he wrote. “Royal authority is sacred; religion and conscious demand that we obey the prince. Royal authority is absolute; the prince need render account to no one for what he orders. Even if kings fail in their duty, their charge and their ministry must be respected. . . . Prices are gods.” Thus monarchs of Europe–particularly Catholic Europe–justified absolute monarchy with religion.

- The Safavid’s use of Shiism. The Safavids rose out of the dissolution of the Timurid Empire, the state formed by the conquests of Timur, also known as Tamerlane. After his death, Timur’s empire fell to warring family members. (One of his descendants, Babur, conquered northern India and began the Mughal Empire.) In Persia, Mesopotamia, and Eastern Anatolia, the disintegrating Timurid Empire opened the way for Shi’ite sects and Sufi brotherhoods to proliferate. Taking advantage of the absence of any centralized state, Ismail—a leader from a prominent Sufi family—conquered most of these areas in the late 15th century and began the Safavid Empire. However, despite unifying Iran (Persia), much of the population did not accept their authority. After converting to Shia Islam, Safavid leaders “sought to install Shiism as the state religion so as to command the loyalty of the population.” The result was a syncretic blend of Shiism and traditional Persian beliefs. Ismail “adopted many of the forms of Persian, pre-Islamic government, including the title of Shah.” He claimed to have descended not only from the Seventh Imam but also to be the reincarnation of pre-Islamic kings and prophets. Ismail’s religious charisma can be seen in his poetry:

Prostrate thyself! (Bow down)

Pander not to Satan

Adam has put on new clothes,

God has come.

Subsequent Safavid leaders continued to fuse Shiism with their political power. They built mosques and appointed prayer leaders in each village to secure Shia beliefs. The Safavids made their empire a safe haven for Shi’a scholars and invited many of them to migrate to their empire. These religious sages depended on the state for support and in turn, recognized the legitimacy of Safavid rule. However, they did not grant them absolute rule over scholarly religious affairs which meant that political and religious leadership would form a dual system of authority, as exists in Iran today. The Shiism of the Safavids would put them at odds with the greater Sunni community. Arab Muslim scholars were not at ease with the Safavid belief that prophecies did not end with Mohammad or that “the souls of old prophets could transmigrate into different human beings at any given time.” These developments also shored up the belief of the Ottomans that they were the protectors of the true form of Islam.

- Mexica or Aztec practice of human sacrifice The sacrificial system of the Aztecs was notoriously violent. Many sacrifices were aimed at maintaining the empire’s economic and social stability and the calendar year was full of systematic sacrifices performed by groups of different tradesmen at specified times. For example, during the month of Etzalcualiztli, fishermen would sacrifice a slave to guarantee heavy yields. Each month priests perform sacrifices tuned to the seasonal cycles of agriculture and rain. But the most elaborate sacrifices were performed on the top of large pyramids where thousands of captives could be killed in a single day. Warriors led their captives from battle to the temple where priests could cut open their chests and remove the heart in as little as twenty seconds. In some cases, a priest would wear the skin of a sacrificed victim for days, and on other occasions limbs from victims were cooked with dried maize and consumed at elaborate banquets.

Historians are not in total agreement about the purpose of these bloody pageants. Some emphasize that they represent the use of terror and fear to coerce obedience to the state. Others demonstrate how the sacrifices, on which many aspects of Aztec civilization depended, maintained the power of the priests and elite classes who carried them out. They seemed also to have brought cohesiveness to the multi-ethnic and tribal components of the expanding empire. The sacrifices at the capital city of Tenochtitlan were “intended to win the loyalty of a relatively small target group, the young men who formed the core of the Aztec army.” The recognition and reward of young warriors provided a cohesive bond among men from varied backgrounds that minimized ethnic and kinship identities. In doing so, the sacrifices brought greater unity and loyalty to the state.

- Chinese emperor’s performance of Confucian rituals Confucianism was always deeply concerned with rituals, and during the Tang dynasty leaders adapted Confucian rituals to legitimize their rule. Later, when the foreign Manchus established the Qing dynasty, they appropriated these rituals in an effort to claim the Mandate of Heaven and elevate the importance of the emperor. Many Confucian rituals involved the imperial family. In fact, it is only a slight exaggeration to say that established rituals proscribed almost everything the emperor did. For example, at the beginning of the spring the Emperor participated in an elaborate ceremony in which he plowed the first furrow of earth and planted the first seed in front of the Temple of Agriculture. No farm work could begin until the emperor completed this ritual. This ceremonial act procured the goodwill of the gods, ensured a plentiful harvest, and linked the vigor of Chinese civilization to the actions of the emperor. The Qing, who were not Chinese but Manchus, adopted this Confucian ritual to connect themselves to the tradition of Chinese emperors who preceded them. It was an act of legitimization.

A Qing ceremony in which the emperor offers sacrifices at the Xiannong Altar, Temple of Agriculture, in Beijing. There were other ways the ruling dynasty used Confucian rituals to legitimize their rule. The sacrifices to Heaven, performed in the northern suburbs of the capital during the summer solstice and in the south during the summer solstice, grew to be the most important rituals. Many rituals of ancestor worship were absorbed into the sacrifices made to Heaven thus creating a close link between the spirits of the ancestors and Heaven. In fact, the Emperor’s ancestors became a link between Heaven and the imperial family. By publicly performing these rituals twice a year, the Emperor was reaffirming the Mandate of Heaven. Some examples of art-legitimizing states are:

- Ottoman miniature painting Influenced by Persian traditions, Ottoman artists developed a rich tradition of courtly art known as miniature painting. As one of the “arts of the book” (along with calligraphy), miniature painting was used to illustrate and embellish government-sponsored manuscripts. While earlier Persian paintings depicted mythical heroes and images of paradise, Ottomans used this art to emphasize their imperial conquests. After his defeat of Constantinople in 1453, for example, Mehmed II adopted visual art to perpetuate his “image as a world conqueror” and identify his capture of the city with some of the most important achievements of past conquests, particularly those of Alexander the Great. Mehmet built an imperial scriptorium and solicited Renaissance artists from Italy to come and share their expertise. Ottoman miniature painting reached its peak in the 16th century when the empire created an official post of court historian. Presiding over a team of writers, calligraphers, illustrators and miniaturists, the court historian produced elegant works of Ottoman imperial history. By the 18th century, when Ottoman conquests came to an end, miniature painting focused on portraits of sultans and illustrations of imperial genealogies. A few of them traced the sultans’ genealogy back through many of the most significant prophets to Adam in the Garden of Eden. Regardless of their topical changes, miniature painting was used by the Ottoman government to reinforce their authority and legitimacy.

- Qing imperial portraits We saw above how important rituals were to the Chinese imperial court. During the Qing dynasty, these ceremonies included the use of art. Imperial portraits of emperors adorned many of the palaces inside the Forbidden City and were an important part of funeral rituals when an emperor died. We see vestiges of ancestor veneration in the fact that some emperors performed ceremonies before portraits of previous leaders of their dynasty and even kowtowed to these portraits. In the public sphere, imperial portraits were utilized to enhance the legitimacy of the emperor. Portraits of emperor Kangxi, for example, often show him surrounded by books or holding a book in his hands, a representation that serves the imperial Confucian ideology that scholarship and command of knowledge merit legitimacy for an emperor. Legitimacy was a crucial factor for Emperor Kangxi. As a Manchu he needed to gain respect from ethnic Chinese; promoting himself as an accomplished scholar helped win the scholar-bureaucrats and gain the Mandate of Heaven in the eyes of many Chinese.

Rulers Using Art: An Important Continuity in State Building

Augustus of Prima Porta. When Caesar Augustus came to power he was welcomed by the monarchists but rejected by the conservative republicans who wanted power to remain with the traditional patrician families. Augustus commissioned this work of art to assuage the fears of those republicans who believed he was a warmonger trying to consolidate his own power at the expense of the old republic. Thus he is shown raising his hand like a strong leader but not brandishing a sword. He is poised for movement but not in a threatening or aggressive way. On his breastplate is the scene of the Parthians surrendering to Rome, one of Augustus’ most important military achievements that overturned a previous humiliation by the Parthians. But this was a necessary military endeavor; the gods look on approvingly, suggesting that Augustus carries out their will. Overall this statue of political propaganda showed Augustus as he wanted to be known rather than how he actually was.

The Qianlong Emperor as the Bodhisattva Mafijusrt. During the reign of the Qianlong Emperor (1736-1796) the Qing dynasty expanded the borders of China farther than they had ever been before. China also became much more multicultural than it had ever been. The Qianlong Emperor used imperial portraits to represent himself to each region in the culture and dress of that region. To the ethnic Chinese (the Han) he had himself painted as a great scholar and promoter of Chinese values; to the Mongols of Central Asia, he was depicted as a traditional warrior of the steppes. The portrait above shows him pictured as the best-known bodhisattva of Tibetan Buddhism, surrounded by Buddhist symbols. For example, he “raises his right hand in the gesture of argument while supporting the wheel of the law in his left. He also holds two stems of lotus blossoms, which serve as platforms for a sutra and a sword, the attributes of Manjusri. He is pictured among 108 deities . . . who represent his Buddhist lineage.”

Emperor Jahangir weighs Prince Khurram. This miniature shows Mughal emperor Jahangir, son of Akbar, weighing his son against valuables such as precious gems, gold, or other important goods. In this tradition, the son’s weight of these goods was given to holy men, used to fund building projects, or distributed to the poor. The picture and the tradition it depicts were part of Akbar’s project of religious tolerance. The “weighing of the ruler’s son” was Hindu in origin and the distribution of wealth to the poor resembled the Muslim practice of almsgiving, one of the pillars of Islam. As Muslim rulers of a predominately Hindu empire, Akbar and Jahangir were dedicated to forging strategic alliances with local Hindu rulers. This painting shows Muslim and Hindu leaders participating together in the ritual. It also demonstrates the wealth, power, and benevolence of the Mughals.

Napoleon in his Study. After a little more than a decade after the French Revolution began, Napoleon Bonaparte had worked his way through the military ranks and proved himself to be a brilliant general. In 1804, taking advantage of the uncertainties and political vacuum of the revolutionary era, Napoleon made himself emperor of France. This portrait depicts Napoleon Bonaparte in that year. The artist emphasizes his role as a tireless and productive statesman. His sword is close by, but at rest on the gilded chair. The candle behind him has burned down to a stump and the clock on the wall reads 4:13 a.m. The object of his tireless labor is on the table, the Code of Napoleon, and the book on the floor is Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans. Its presence suggests Napoleon be included with the great leaders of antiquity.

State-Building and Monumental Architecture

As we have seen since the earliest empires, the territorial growth of states invites the problems of ruling a large multi-ethnic empire. The most successful states found ways to incorporate ethnic and cultural minorities in a way that permitted the state to benefit from their presence while at the same time limiting their political influence. Between 1450 and 1750 there were several examples of states attempting this balancing act.

Ottomans and their non-Muslim subjects

After the fall of Constantinople in 1453 the Ottoman Empire absorbed the former Byzantine lands and the number of Christians under Ottoman rule greatly increased. By the middle of the 1500s, the non-Muslim population of the empire reached about 40%. To deal with the increasing diversity of the Empire, Mehmet II introduced what would later be called the millet system. Each millet, from the Arabic word for the nation, was an autonomous zone made up of a particular religious group. Each millet was permitted to choose its own leader, practice its own religion, and live by its own religious orders or rules; Sharia law did not have an effect on a non-Muslim millet. For example, Orthodox Christians and Jews each had their own respective millets and lived according to their own customs. An influence on the development of non-Muslim millets was that members were not allowed to hold military or political posts. Thus their impact on the Islamic character of the Empire was limited. Consequently, Christian and Jewish millets turned to the development of craft skills, finance, and brokerage. They became important intermediaries in trade negotiations with merchants outside the empire benefitting the Ottoman economy.

Manchus and their Chinese subjects

As mentioned above, the Qing dynasty expanded Chinese territory larger than it ever had before and ruled a population of 450 million people. Unlike previous Chinese dynasties, the Qing did not impose the Chinese language or culture over their subjects and thought of China as just one part of a larger Manchu empire. They adopted a policy of “ruling different people differently,” allowing local languages, customs, and in some cases, permitting local leaders to maintain leadership positions. Some groups had more privileges than others. Manchus, of course, were the most favored group but Chinese were allowed to take governing posts in the Confucian bureaucracy along with Manchus. The highest point to which a Chinese civil servant could rise was an executive position known as a “grand secretary.” These administrators had no policy-making power; however, they served as channels of communication “by ratifying and forwarding ‘memorials,’ reports sent to the emperor from other central and field offices.” The highest central administrative positions in Beijing, of course, were reserved for Manchus. Allowing Chinese to earn positions in the bureaucracy through civil service examinations rendered Manchu rule more acceptable for Chinese. To prevent the Chinese from dominating the bureaucracy, it was much easier for Manchus to gain appointments and rise through the ranks.

Spanish America and the República de Indios

In colonial America, Spanish administrators sought to adapt and impose the social structure of Iberia. Back home, society was organized into large corporate groups with different levels of rights and privileges adhering to each group rather than to individuals. In the New World, the Spanish likewise divided the population into two primary groups. The first group was the república de españoles comprised of all Iberian-born people, Spanish creoles, and anyone else of mixed Spanish race. The other group was the república de indios made up of the non mestizo indigenous population. This separation was initially made to protect indigenous people from the harness of the Spaniards; they were divided into independent communities ruled by their own elites, and they enjoyed their own separate system of courts and laws. The system failed because of Spanish demand for indigenous labor. República de Indios were required to supply labor through the mit’a system to American silver mines. They became the target of the labor draft in Mexico known as the repartimiento which supplied labor to commercial farms, mines, and select private enterprises. Their required tribute payments became an important source of revenue for the Spanish colonial governments. The continued flow of people between the república de españoles and the república de Indios eventually blurred their distinctive identities.

Empires: Belief Systems

The Protestant Reformation marked a break with existing Christian traditions and both the Protestant and Catholic Reformations contributed to the growth of Christianity. Christianity In this era Christianity became more diversified and spread across the globe. The impetus for these changes began in Western Europe where the unity of Christian civilization was shattered by the Protestant Reformation. The printing press made the Bible available to countless Christians, and many of them took it to be a higher authority in their lives than the Pope and the hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church. Believers who “protested” the church and broke from Catholicism became known as Protestants. Owing to their belief that Christians can read and interpret the Bible for themselves, Protestants quickly splintered into many subgroups based on varying interpretations and practices. The Protestant Reformation quickly became political as some European monarchs left the Catholic Church only to free themselves from the Pope’s authority and become more autonomous.

The Catholic Church responded to the Protestant Reformation with the Council of Trent, a large meeting in which they affirmed their Catholic beliefs, answered criticisms of Protestants, and reformed some Catholic practices. From a global perspective, the most important impact of the Council of Trent was the decision to convert people in newly discovered and accessible lands to the Roman Catholic faith. The Order of Jesuits was created for this missionary purpose. After intense training in philosophy, theology, and survival, Jesuits went out across the globe seeking converts and often endured severe hardships and even executions. Despite their zeal, they had little success in Asia except for the northern Philippines which remains predominately Catholic to this day.

The Jesuits had much more success in Latin America. In Brazil, they organized people into villages, built schools for children, and created a writing system for the local languages. The seventeenth century saw an increase of Jesuit missionary activity across Latin America. They set up missions in Peru, Colombia, Venezuela and Bolivia. As early as 1603 there were 345 Jesuit priests in Mexico alone.

Political rivalries between the Ottoman and Safavid empires intensified the split within Islam between Sunni and Shi’a. The Sunni-Shia divide in Islam that emerged in the previous period grew more intense in this era. The epitome of this conflict was the struggle between the Ottoman Empire, which was Sunni, and its Shia neighbor, the Safavid Empire. The territorial struggle between these two Muslim empires culminated with the Battle of Chaldiran in 1514. At this battle in present-day Iran, the outnumbered and poorly equipped Shia Safavids were defeated by the Sunni Ottomans. Firearms were a prominent reason for the Ottoman victory and they experienced a period of expansion after the Battle. The Safavids learned the importance of firearms and became a “gunpowder empire.” More importantly, the spread of Shia Islam was stopped and this sect continued as a minority sect of the Muslim religion.

A major force in the spread of Islam during this era was Sufism. This sect of Islam emphasized the experiential and mystical approach to God over formal practices and creeds. Sufis sought emotional encounters that brought them into union with God. Organized into Orders, each group had is own habits and rules and usually formed around a charismatic holy man. Sufism served to spread Islam in two ways; because they begged for food and did not own homes, Sufis were wandering mystics and became de fact missionaries. Secondly, their emphasis on experience rather than doctrines allowed them to adapt to many host cultures and form syncretic belief systems. In Southeast Asia, for example, Sufis were accepted by the Hindu Bhaktis who had their own tradition of experiential religion. Thus Sufism was absorbed into a wider devotional movement that transcended religious faiths. In West Africa, where Sufi Orders became an important institution in African society, Sufism became an essential element of Islam’s spread and integration. In these Orders, Sunni and Shia Muslims, heretics, and traditional spiritualists all came together. Sufi mystics were often well-versed in Islam as well as in the spiritual ways of traditional African religions. Consequently, it is not surprising that Islam in West Africa tended to remain highly syncretic. Sunni Ali, the founder of the Songhai Empire, claimed to be a Muslim but continued to practice traditional religious rituals and sacrifices and sought legitimacy through them.

Sikhism developed in South Asia in the context of interactions between Hinduism and Islam. Islam blended with local cultures in Southeast Asia as well. The prophet Mohammed showed up as a character in Hindu epics and local folklore. In Indonesia, the selamatan, a local feast of reconciliation, was used by Muslim leaders to convert people to the new faith. Conversion stories took on traditional characteristics, such as accompanying miracles and signs. In Javanese culture, these miracles were necessary to establish the leader as a channel of communication between God and the people. As the Islamic Mughal Dynasty formed in South Asia, an enormous amount of religious syncretism formed. A new world religion, Sikhism, combined Islam’s notion of the oneness of God with the Hindu concept of inclusiveness. Although it did not endure, Akbar attempted to create a new faith by combining elements of Hinduism, Islam, Christianity, and Zoroastrianism. In the arts, Persian, Hindu, and Muslim styles blended to form a distinctively Mughal form of painting.

TRANSOCEANIC CONNECTIONS

Technological Innovations from 1450 to 1750

The most significant change in global trade between 1450 and 1750 was the rise and involvement of the Europeans. Beginning with Portugal and Spain, European countries would commission the exploration, charting, and colonization of a huge portion of the world. The advancements that enabled them to do this, however, did not originate in a vacuum. Europeans adapted, improved, and synthesized the use of technologies and knowledge that came to them from elsewhere. European technological developments in cartography and navigation were built on previous knowledge developed in the classical, Islamic, and Asian worlds.

Navigation Technologies A mariner’s astrolabe. Islamic civilization had long possessed the need for astronomical and geographic knowledge. Muslim schools were expected to pronounce daily prayer times, calculate the exact time of the holy month of Ramadan, and provide the faithful with the direction of Mecca for the purpose of prayer. To address these religious matters they developed the astrolabe which enabled them to solve “300 types of problems in astronomy, geography, and trigonometry.” Through Muslim Spain, the astrolabe entered Christian Europe. Borrowing the basic principles of the Islamic astrolabe, the Portuguese created the mariner’s astrolabe, an instrument whose functions were limited to and designed specifically for the purpose of navigation. At sea, the mariner’s astrolabe helped ships determine their latitude by aligning the instrument with the sun or a known star.

Cartography The sea voyages of the Europeans in this era could not have taken place without a revolution in the craft of cartography, or map-making. European maps in the Middle Ages, called T-O maps because of their shape, were not intended as tools for navigation. These maps often placed Jerusalem in the center of the world and divided the world into the domains of Noah’s three sons. Hence they were qualitative maps intended to make a religious statement about the world from a Christian point of view. They declared what was religiously important but were useless in bringing sailors back to port.

This changed with European contact with Byzantine and Islamic influences that had been increasing over the previous few centuries. Although the writings of the Greek cartographer Ptolemy (90-168 C.E.) had been making their way into Europe in the previous period, few Europeans read Greek. With the increase of available classical authors and their translation into Latin, a new interest in Ptolemy’s work emerged.

Combined with the growing desire for trade, navigation, and cartography attracted some of the best academic minds of the 15th century who began to view the world, like Ptolemy, in a quantitative way. They believed mathematics corresponded with the actual way the world was. A change in mentality meant that the world was now conceived in a mathematical and rational way. Cartography was concerned with making maps that resemble the features of geography as they actually existed rather than making a theological statement about the world.

Merchants could now use maps to plot new routes to and from desired locations and their experiences and information were in turn applied to the latest maps. The craft of this new quantitative method of map-making and the training required for the new instruments of navigation were taught in the city of Lisbon, Portugal.

Innovations in Ship Design Another European advancement based on previous technologies was the caravel, a light, fast, and maneuverable ship first devised by the Portuguese. (Columbus constantly praised his favorite ship, the Niña which along with the Pinta seemed to be a caravel.) Lighter, requiring a smaller crew, and able to carry more cargo than the typical oar-driven Mediterranean ships, the caravel adopted the lateen sail first pioneered by Arab merchants in the Indian Ocean. This gave these ships the ability to tack into the face of the wind. The caravel was able to carry a large cargo with an inordinately small crew, thus decreasing the cost of shipping and increasing profits. Developing about a century after the caravel was Note the indirect route (in red) of the return to Portugal from the western coast of Africa. The westerlies made this the more efficient route. The Spanish galleon was a large multi-deck ship with at least three or four masts. The forward sails were large rectangular power sails with the last mast usually carrying a lateen sail. These ships were the primary vessels of the Spanish Treasure Fleet and were capable of carrying an enormous volume of cargo. They carried most of the slaves across the Atlantic via the dreaded Middle Passage. Europeans were the first to mount firearms on their ships, outfitting their caravels and galleons with broadside cannon. Thus armed, these ships gave Europeans the capacity to project unprecedented power.

Knowledge of Wind and Sea Currents Europeans were also aided by their growing familiarity with the global environment and their adaptation to it. The Portuguese learned that the most efficient maritime route between two points is not always a straight line. This could involve fighting the wind and sea currents. Consequently, they developed a strategy known as the volta do mar, or turn of the sea. Often going far out of their way, the Portuguese and other European sailors learned instead to work with the currents. For example, when Vasco da Gama sought a route to the Indian Ocean around Africa, he sailed nearly to the coast of Brazil before he caught the westerlies that took him around the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa. Knowledge of such trade winds allowed sailors to be more efficient by using, rather than going against, the grain of nature.

Exploration: Causes and Events from 1450 to 1750

Unaffected by the ravages of Europe’s 100 Years War and Spain’s civil strife, Portugal became the first European nation to embark on a program of exploration. King John’s son, Prince Henry, was motivated by a crusading zeal to convert heathens to Christianity and an economic zeal to gain access to west Africa’s legendary sources of gold. Henry’s capture of the Muslim city of Ceuta in 1415 opened the western coast of Africa to Portuguese exploration, and by the year of Henry’s death in 1460, his country had arrived in Guinea on Africa’s western coast. Soon African gold was flowing by sea from west Africa directly to Iberia rather than across the trans-Saharan caravan routes. Algiers and Tunis in north Africa were economically devastated by this rerouting of trade. Portugal got rich. As contacts with west African societies continued the Portuguese began trading in ivory and slaves as well.

After a dispute with his father, Prince Henry returned home to Portugal but avoided the capital of Lisbon where he could have easily gained a comfortable royal job. Instead, he settled in the remote coastal town of Sagres which he turned into a center of navigational studies and cartography. Now called Prince Henry the Navigator, he collected fresh information from newly arrived sailors to produce the most current maps possible. The compass, thought by many Europeans to be driven by occult powers, was disenchanted with superstition, and its use expanded and refined. Since initial Portuguese voyages traveled north and south exploring Africa, more precise means of measuring latitude were researched. Borrowing elements of Arabic shipbuilding, Prince Henry and his engineers designed the famous caravel, mentioned above. All the elements needed for global exploration were brought together by Prince Henry at Sagres. Portugal was poised to take the lead, albeit brief, in the exploration and exploitation of the globe.

Equipped with new maritime instruments and knowledge, the Portuguese accomplished many “firsts” in global exploration. In 1487 Bartholomew Diaz sailed his caravel around the southern tip of Africa, the first European to do so (his crew refused to press on to India). Then Vasco da Gama became the first to sail all the way to India in 1498. When he turned to Portugal the following year, the spice cargo in his ship was worth 60 times the cost of his voyage. Europeans had found the elusive water route to the lucrative Indian Ocean trade network. The Portuguese strategy in the Indian Ocean was to dominate trade through the use of firepower, intimidation, and brutality. In the long run, they were never able to completely monopolize this network but did succeed in building a trading-post empire which gave them a significant share of the spice and slave trade. With over 50 trading posts from southeast Asia to Africa’s west coast, they attempted to force merchants to call at these ports and pay duties. They also required merchants to purchase passports from them; sailors caught at sea without one were mutilated and had their cargo confiscated. Despite these grand plans, the Portuguese had neither the manpower nor the fleet to carry out their demands. Many Indian Ocean merchants took their chances and sailed without passports or paying dues at Portuguese trading posts. And the Spanish, English, and Dutch sailors hired by the Portuguese to work their fleet took the knowledge of the seas back to their respective countries who were organizing their own expeditions to Asia. The Portuguese began the explorations but were soon to be strong-armed out of the way by their European neighbors.

In 1476 a 25-year-old Christopher Columbus washed onto the Portuguese shore with a broken oar he had used as a float. The cargo ship he worked on had been sunk by a French fleet near Gibraltar. As fortune would have it, the place where he reached the shore was only a few miles from Sagres, the location of Prince Henry’s research center of navigation and cartography. Having grown up in Genoa on the Italian coast, Columbus had long possessed a fascination with sailing. But his time in Portugal, particularly Lisbon, would prove to be the most formative for what he would unwittingly accomplish.

The idea that sailing west would lead one to Asia was not new. What was novel about Columbus was his conviction that the distance between Europe and Asia to the west was not significant. Basing his argument on Marco Polo’s description of the distance across Eurasia and Ptolemy’s longitudinal calculations, Columbus vastly underestimated the distance of a western route to Asia. Nevertheless, he set out enthusiastically to convince the monarchs of Europe he was right in order to obtain funding for his journey. After a series of rejections, Ferdinand and Isabella of the newly united Spain decided to pay for Columbus’ voyage. In October of 1492, he sighted land in what he believed to be Asia. Columbus would make four voyages across the Atlantic and seems to have died not knowing that he had failed.

Columbus did not actually discover anything, nor was he the first European to make this crossing. Nonetheless, his journey is very important historically because he initiated a world-transforming encounter between two hemispheres of this planet. There would be profound cultural, demographic, political, and social consequences.

When it was realized that Columbus had not succeeded in finding a route to Asia, the quest did not end. North Atlantic crossings increased as European explorers sought to exploit the wealth of the New World and continue to find a way across it. The waters off the eastern coast of North America were teeming with fish and some men made fortunes shipping salt-cured cod to Europe and the Caribbean. Explorers such as Champlain from France earned huge profits by sending beaver pelts back to Europe. But like many others, Champlain’s motivation was not merely conquest or profit for their own sake. The furs were used to fund his ongoing obsession–the discovery of a western route to China.

The new global circulation of goods was facilitated by royal chartered European monopoly companies that took silver from Spanish colonies in the Americas to purchase Asian goods for the Atlantic markets, but regional markets continued to flourish in Afro-Eurasia by using established commercial practices and new transoceanic shipping services developed by European merchants.

According to the long-standing conventions of Indian Ocean trade, no single power controlled the entire network and the seas were free and open to any merchant. The Europeans would attempt to change this. Beginning with the Portuguese, Europeans attempted to install a Mediterranean system of trade that used military might to divert trade through trading ports they controlled. There it could be taxed. They did not really bring any items of their own to trade or add value to the sum of trade in this region. Instead, they attempted, in a parasitic way, to extract benefits from the host network into which they forced themselves.

We saw in the previous period (600-1450) that the creation of a common currency in China facilitated trade in that region. Widely accepted currencies speed up transactions and provide a standardized way for merchants to measure the value of products. In this period the use of a common currency expanded from regional to global use. The Spanish peso de ocho, or “piece of eight,” was the first currency in history to be used globally.

From the start, superior firepower allowed them to accomplish much. The Portuguese stormed the Swahili city of Kilwa and threw out its Muslim leaders. Commander Alfonso Albuquerque seized Malacca in 1511 (the Dutch would take it from Portugal in 1641). The Portuguese attempted to close the Red Sea to trade to stop this “leak” of trade through their fingers into the Mediterranean via Egypt. Breaking traditional customs of tolerance, the King of Portugal asked the leader of Calicut to expel all Muslims from his kingdom. But Portugal’s ambitions were grander than its ability to enforce its demands. Rather than an all-out conquest of the region, they established a trading post empire (mentioned above) to profit from goods as they moved from one area to another. Indeed, by the end of the 1500s they had integrated with the normal political and economic climate of the region. Other European countries would implement the same strategy. The Dutch, for example, found that working within the existing system could produce for them the highest profits. They made a fortune charging fees to transport items from one Asian area to another. The European powers were never able to establish genuine and lasting monopolies in the Indian Ocean. This is in stark contrast with their experiences in the New World.

This currency was the product of Spain’s mining of enormous amounts of silver in the New World. In present-day Bolivia and Mexico, they discovered massive deposits of silver, including a mountain full of silver at Potosi. After the purest veins of silver were quickly strip-mined production slowed; then the Spanish introduced the amalgamation method of using mercury to extract silver from ore. Production soared. In two centuries the silver mines of the Spanish New World produced 40,000 tons of silver. The industrial centers that grew around these mines minted 2.5 million silver coins per year. The peso de ocho, worth about 80 US dollars today, gained acceptance around the world and lubricated global trade on an unprecedented level. Mughal India wanted Spanish silver for payment for its pepper sales, and this surge of silver funded Shah Jahan’s construction of the Taj Mahal. Much of the Spanish silver ended up the hands of the Chinese, who had no desire for European products but readily accepted silver as payment for its coveted exports. The peso do ocho was even accepted currency in the United States until the Coinage Act of 1857.

In the early 1600s European countries found new methods of financing exploration and business. Since trading ventures were too expensive for most individuals to fund, investors began to pool their resources together into organizations called joint-stock companies. The most famous of these, the British East India Company (EIC), began in 1600 when the British government gave 218 London investors a royal monopoly of all trade east of the Cape of Good Hope. Established about one year later was the Dutch East India Company, known as the VOC. They were initially a much larger and wealthier rival of the EIC, with 10 times the capital resources of its British counterpart. Joint-stock companies proliferated. The Dutch West Indies Company traded in the New World and founded New Amsterdam, today New York City. And the Virginia Company of London was given a monopoly on the mid-Atlantic coast of North America.

Joint-stock companies were an improvement over traditional partnerships because of something called limited liability. In a partnership, investors pool their resources together and share the profits or losses collectively. In the case of a shipwreck or some other calamity, however, investors would owe more than they put in and could be driven to bankruptcy. But the limited liability of a joint-stock company meant that an investor could never lose more than what he paid in. With risks thus limited but the potential for profit still high, joint-stock companies attracted thousands of investors willing to put up the money, called stock, in these ventures.

Voyages funded by joint-stock companies were more efficient and profitable than those funded by monarchs. Unconcerned with religious conversion, their voyages were streamlined to produce as much profit as possible in order to please investors and attract more capital. Thus countries such as Spain and Portugal, in which the king financed business, could not compete with the more efficient business practices of companies. Spain endured only as long as it could drain the New World of its silver reserves.

Since the classical age, several major trade routes dominated trans-regional trade. Political, environmental, and demographic changes altered the ebb of flow in the volume of trade and gave each a turn at being the dominant trade route. These major routes coexisted for most of this time and no major new networks were added. Between 1450 and 1750, however, an entirely new trade route emerged and became the world’s dominant network of exchange. The Atlantic System connected the old and new worlds in a triangular pattern across the ocean. A truly global system of trade was established.

In an effort to make trade as efficient as possible, ships in this triangular pattern never sailed empty. From Africa, they sailed across the Atlantic to the New World with slaves. After selling the slaves, they sailed to Europe with sugar, tobacco, and rum. After loading their ships with alcohol, metal items, and guns, they said to Africa’s west coast to trade these things for slaves and begin the circuit all over again.

Despite all the dramatic changes in labor during this period, Africa continued to supply slaves to the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean as it did in previous periods. Records of the slave trade in Africa date back to 2900 B.C.E. when slaves were transported from Sub-Saharan Africa to Nubia. [8] As the slave trade grew tremendously in the Atlantic system to supply plantation labor in the Americas, the movement of African slaves to the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean regions was an important continuity with the past.

The Portuguese colony of Brazil was the first to implement the plantation system in the New World. A plantation is a large commercial farm used to grow a single cash crop for export. First tobacco, and then sugar became the most lucrative crops in this system. However, indigenous labor did not work well as many native Americans succumbed to diseases carried by the European plantation managers. Europeans looked to Africa. With the growth of the plantation system, the demand for African slaves increased. Over 10 million were transported across the Middle Passage of the Atlantic System.

Many Europeans came to the new world to make a fortune. Without labor, the land they gained had no value in accomplishing this goal. Economic success depended on the ability to mobilize a large labor force in the service of the European colonizers. Consequently, they established a wide range of coerced labor systems in the Americas:

- The encomienda This Slavery in Brazilsystem was modeled after the reconquest of Iberia. In Spain, the conquistadors were granted access to Muslim labor in the areas they reconquered for the monarch (recall that much of Spain was under Muslim control for centuries). After its success in Europe, the Spanish attempted the same practice in the Americas. Land grants, called encomiendas, were given to Spanish conquistadors and soldiers and they were free to exploit the labor of the people inhabiting the land entrusted to them. Under Philip II of Spain, the encomienda system was instituted in the Spanish Philippines as well. In the Americas, the system went into decline as many natives died of diseases in close contact with Europeans.

- The mit’a system As disease rendered the encomienda system unworkable, the Spanish and Portuguese adopted a labor system from the Indigenous people themselves. The mit’a system developed in the Inca Empire as a method of rotating groups of workers in the service of the state. When they were not working on their family farms, men between the ages of 15 and 50 would provide their labor to the empire as a form of tax payment, or a corvée system. The Spanish adopted this system of labor and applied it to several contexts, especially their silver mining projects. Villages controlled by Spain had to provide a set number of people to the Spanish for labor in the mines.

- The hacienda Like the encomienda and the mit’a system, the haciendas generally exploited local indigenous labor. However, the hacienda was a private estate, often the result of a land grant given to an individual by the monarch. Another difference is that the hacienda produced food and goods primarily for local consumption. They tended to be self-sufficient estates although many of them were economically connected to nearby encomiendas with which they traded food items and hand-produced goods.

- Chattel slavery Chattel slavery is what most people think of when they hear the word slavery. It is the form of labor in which the laborer is most dehumanized as he or she is considered solely as private property of the owner. Chattel slaves can be bought and sold at the owner’s discretion, are uncompensated, and have little chance of gaining freedom. As mentioned above, Africa provided the chattel slaves to the Americas predominately after sugar plantations, begun by the Portuguese, spread across South America and the Caribbean.

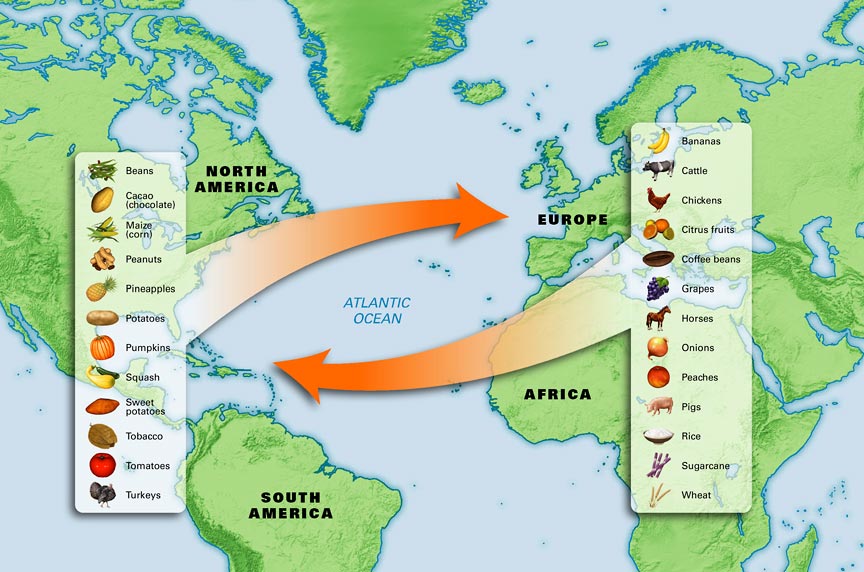

The Columbian Exchange

The new connections between the Eastern and Western hemispheres resulted in the Columbian Exchange. After the voyage of Columbus, the two halves of the planet learned that each other existed. As networks of trade and communication expanded to include both hemispheres, items from one side made their way over to the other side in a process of exchanges that lasted several centuries. In the 20th century a historian named this process of intentional and unintentional sharing the Columbian Exchange.

A significant part of the exchanges that took place after Columbus was biological in nature. Because of their long history of contact with farm animals, Europeans were carrying microorganisms to which they had developed immunities. The native Americans did not have these immunities and were thus highly susceptible to the diseases caused by the microorganisms. New encounters between Europeans and native Americans caused the spread of viruses such as measles and smallpox with catastrophic results. Natives died by the millions. In central Mexico, pandemic diseases killed 60 to 90 percent of the population. When the Tlaxcalan people sided with the Spaniards against the Aztecs, Tlaxcala paid a heavy price. The disease they caught from their Spanish allies killed up to 1,000 of them daily, with a total of about 150,000 deaths. In addition to smallpox and measles, Europeans also inadvertently spread cholera, malaria, influenza, and bubonic plague in the New World. The decimation of native Americans due to these diseases played a large role in the Spanish conquest of the mighty Incan and Aztec empires.

The Columbian Exchange also diffused new crops from the Americas to locations throughout the world. Potatoes were transplanted to places like Europe, Russia, and China. Because they produce heavier yields than cereal grains and can be cultivated in higher altitudes, potatoes led to increased surpluses of food. About 25% of the population growth in Afro-Eurasia between 1700 and 1900 can be attributed to the cultivation of potatoes. China, for example, experienced rapid population growth after potatoes were widely cultivated there. Tomatoes and hot chili peppers were also transplanted from their place of origin in South America to Afro-Eurasia. Today, the cuisines we characteristically associate with Italy and Asia are unthinkable without tomatoes and hot peppers, respectively.

Some New World plants were cultivated as cash crops and exported to the Old World. The Europeans learned about tobacco from the Native Americans. Although the natives did not use it recreationally, its use became widely popular with Europeans in the New World and back home. In the English colony of Jamestown, tobacco leaves were used as currency and the exporting of tobacco as a cash crop is credited with having saved colonial Virginia from ruin. A more important cash crop than tobacco was sugar. Indigenous to Southeast Asia, sugarcane was brought to the Caribbean by the Spanish early on. The demand for sugar in Europe grew, as it was a more convenient and potent sweetener than what was available to them. The Portuguese introduced the plantation system in Brazil to grow sugarcane. Then in the early 17th century, a discovery was made that dramatically increased the cultivation of sugar. Plantation slaves discovered that molasses, a byproduct of the production of sugar that was often discarded, could be distilled into alcohol. This new product, Rum, meant that sugarcane could produce two highly profitable products and had virtually no waste. Entire forests were cleared to grow sugarcane and the plantation system proliferated across the Caribbean. This in turn created a tremendous demand for slaves. The cash crop of sugar–and to a lesser extent tobacco–increased the slave trade of the Atlantic system.

Another aspect of the Columbian Exchange was the introduction of Old World domesticated animals to the New. Europeans brought pigs, cows, sheep, and cattle to the Americas as well as rodents like rabbits and rats. With wide open spaces and virtually no natural predators, these animals quickly multiplied across the Americas; by 1700, herds of wild cattle and horses in South America reached 50 million. In North America, tribes like the Navajo became sheepherders and began to produce woolen textiles. The abundance of cattle increased the amount of meat in New World diets and provided them with hides. The introduction of horses had an even greater effect. They dramatically increased the efficiency of hunters and warriors, and tribes like the Comanche, Apache, Blackfoot, and Sioux grained greater success in hunting the buffalo herds on the plains of North America. Alongside these animals brought by Europeans, slaves brought new plants to the New World such as yams, okra, and black-eyed peas. Soon they became common foods that took the place of most indigenous crops, except maize (corn).

New World crops that were transplanted to Afro-Eurasia improved the variety and nutritional content of the population. The coming of potatoes, sweet potatoes, and maize to the Old World “resulted in caloric and nutritional improvements over previously existing staples.” Tomatoes and peppers not only added vitamins and improved the taste of Old World diets; they also contributed to the development of regional cuisines.

New World food crops made different demands on the soil than crops that had been cultivated for centuries in the Old World. Fields whose fertility had declined with tireless planting of traditional crops were given new life when New World crops arrived. The new crops also had different growing and harvest times. Thus New World crops complemented crops already grown in the Old World creating more varied, nutritional, and abundant food production.

The presence of the Europeans had negative effects on the environment of the New World. Now that trade was global, there was an urgent need for a larger number of ships. Easily accessible forests in Europe had long since disappeared, so Europeans looked to the seemingly unlimited timber of the New World for their shipbuilding needs. Further contributing to this deforestation was the single cash-crop nature of the plantation system. Tremendous profits could be made by converting huge tracks of land to sugar or tobacco production. This required clear cutting forests which led to increased erosion and flooding.

Deforestation allowed cattle and pigs, which Europeans had brought to the New World, to proliferate tremendously. Unhindered by thick forests, livestock was free to roam and scavenge. They destroyed native farms, eating harvests and trampling crops. Europeans who practiced subsistence farming also had a negative effect on the environment. Instead of rotating crops, as they did in Europe where land was scarce, they practiced slash-and-burn agriculture in the New World where land was abundant.