The Late Medieval World

- The spread of religion, aided by the increase in trade, often acted as a unifying social force. Throughout East Asia, the development of Neo-Confucianism solidified a cultural identity. Islam created a new cultural world known as Dar al-Islam, which transcended political and linguistic boundaries in Asia and Africa. Christianity and the Catholic Church served as unifying forces in Europe.

- Centralized empires like the Arab Caliphates and the Song Dynasty built on the successful models of the past, while decentralized areas (Western Europe and Japan) developed political organization to more effectively deal with their unique issues. The peoples of the Americas saw new, large-scale political structures develop, such as the Inca Empire in the Andes and the Mississippian culture in North America.

- The movement of people greatly altered the world politically and demographically. Traveling groups, such as the Turks and Mongols, disrupted much of Asia’s existing political structure. Turkic peoples founded the Mumluk and Delhi Sultanates. The recovery from the Mongol period introduced political structures that defined many areas for centuries to follow.

- There was tremendous growth in long-distance trade. Technological developments such as the compass improved shipbuilding technology, and gunpowder shaped the development of the world. Trade through the Silk Road, the Indian Ocean, the trans-Saharan routes, and the Mediterranean Sea led to the spread of ideas, religions, and technology. Interregional cultural exchanges, represented by early world travelers like Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo, increased due to the Mongol Conquests.

- War, disease, and famine caused massive social and political upheaval throughout Eurasia. The Black Death killed over a third of the European population, and the resulting labor shortfall increased the bargaining power of peasants, diminishing the system of feudalism. The Mongol Conquests led to a massive death toll from Korea to Russia to the Middle East, weakening many regions for centuries to come as European powers expanded outward.

- Western Europe and China saw significant economic and political recoveries. The Italian city-states grew prosperous enough to support the burgeoning Renaissance, which was partly inspired by ancient Greek works recovered from Islamic scholars. The Ming Dynasty experienced a cultural flowering that resulted in great works of art. The Ming also supported major naval expeditions by Zheng He.

CULTURAL DEVELOPMENTS AND BELIEF SYSTEMS

- Neo-Confucianism: Popular during the Tang Dynasty; fused elements of Buddhism and Confucianism.

- Catholic Church: The largest of the three main branches of Christianity; centered in Rome and led by the pope; found most often in Europe, the Americas, sub-Saharan Africa, and parts of East Asia.

- Eastern Orthodox Church: The third largest of the three main branches of Christianity; originally based in the Byzantine Empire; found most often in Russia, Eastern Europe, the Balkans, and parts of Central Asia.

- Shi’a: One of the two main branches of Islam; rejects the first three Sunni caliphs and regards Ali, the fourth caliph, as Muhammad’s first true successor; most commonly found in Iran, but otherwise constitutes 10 to 15 percent of Muslims worldwide.

- Sunni: One of the two main branches of Islam; commonly described as orthodox and differs from Shi’a in its understanding of the Sunnah and in its acceptance of the first three caliphs; is by far the most common branch of Islam worldwide.

Developments in Europe

Feudal Society

After the fall of Rome, Europe, specifically Western Europe, was dominated by smaller kingdoms and regional powers. Between 1200 and 1450, many of the modern states today were formed as powerful kingdoms replaced localism. In places like France and England, the people were feudal. Feudalism is a political, economic, and social hierarchy that helped organize land, work, and people’s roles. At the top is the monarch, often a king. He basically “owned” all of the lands and would grant land, called fiefs, to elites called lords. The lords would then grant some of their own lands to other individuals. Those who were granted land were called vassals. Vassals owed food, labor, and military service to the lords above them. Many kings and lords, as well as the church, would hire knights to protect their wealth and power. The land was sometimes worked on by those who were not the lords to others. These serfs were not slaves but owned no land, thus were very tied to the lord who granted them permission to work the land. Serfs and the manors they worked on would practice the three-field system, where the farmers were careful to not overuse the soil by rotating wheat, beans, and/or let the land lay fallow (unused) during the harvest.

Resources:

Comparing Labor Systems in late Middle Ages

Regionalism to Kingdoms

Between 1200 and 1450, regional kingdoms of France, England, and the Holy Roman Empire became solidified. In the beginning, each power was tied to the Catholic Church and feudal. However, over time, the Catholic Church began to lose influence leading to the Reformation of the 1500s. Feudalism also weakened as monarchs like King Philip II of France created a larger bureaucracy that worked with a legislative body called the Estates-General. The Holy Roman Empire lay where modern-day Germany is today. Unlike France, regional kingdoms with powerful princes and the church had a lot of power versus the central government. The Concordat of Worms (Worms is a German city) allowed the Pope of the Catholic Church to appoint bishops in HRE but gave the king the ability to veto those choices. Unlike France, English kings were being checked by the nobility. King John was forced to sign the Magna Carta, giving the people more rights in trials and taxation. The English Parliament will eventually form to be a strong legislative body. Over time, the competition for trade, land, and resources led the English and French to war. The Hundred Years War is an example of this type of conflict. Conflicts like this created a new spirit of nationalism and an end to feudalism.

Resources:

Religious Conflict

This era saw a lot of religious tension in Europe. The predominantly Christian Europe saw the spread of Islam up the Iberian peninsula as a threat. Charles The Hammer Martel stopped its advance at the Battle of Tours in southern France. By 1492, the Catholic Church had expelled the Muslims from Spain in the Reconquista. The Catholic Church started the Crusades in order to take the Holy Land back from the Muslims. The series of Crusades saw the Crusaders also attacking the Orthodox Christians in Constantinople. In the end, the Crusades failed to win back Jerusalem, rather it just weakened the Catholic Church and increased the power of regional monarchs. However, this cross-cultural contact did slowly awaken Europe to the science and mathematics that the Islamic world had been developing.

The Renaissance

By 1450, Europe saw an increase in literacy, urbanization, and connection to the global community. At one time, the only literate people of Europe were monks and other men tied to the Catholic Church. Gutenberg’s printing press will change this. At one time, Europe was closed from trade with the rest of the world. The Crusades and Mediterranean trade will end this. This will see the beginning of the Renaissance. The Renaissance, or “rebirth”, was a period of European cultural, artistic, political, and economic activity following the Middle Ages. Generally described as taking place from the 1300s through the 1600s, the Renaissance promoted the rediscovery of classical philosophy, literature, and art. Some of the greatest authors, scientists, and artists in human history thrived during this era, while global exploration opened up new lands and cultures to European commerce.

Europe in the Global Middle Ages

CIVILIZATIONS IN THE AMERICAS

When talking about North, Central, and South America in the time period before 1200, the lack of unity and consistency needs to be understood. Because of its limited population and large amount of land, Native Americans were able to live in smaller, regional tribes. Some of these tribes developed into larger civilizations and even empires. The Mississippian culture is a civilization in modern-day southeastern United States. The Mississippian people created large earthen mounds demonstrating their unity to build large monumental structures. Instead of tracing family lineage through the father’s family, the Mississippian culture was matrilineal, passing social standing through the mother’s bloodline.

Connections and Developments in the Americas

Feudal Japan: The Age of the Warrior

While most samurai warriors were men, some women were renowned for their skill in battle. A monument was erected to honor Nakano Takeko — a female warrior — at the Hokai temple in Fukushima prefecture because she asked her sister to behead her rather than die dishonorably from a gunshot wound in captivity.

Being a warrior in feudal Japan was more than just a job. It was a way of life. The collapse of aristocratic rule ushered in a new age of chaos — appropriately called the Warring States period (c.1400-1600) — in which military might dictated who governed and who followed.

The samurai warriors, also known as bushi, took as their creed what later became known as the “Way of the Warrior” (Bushidô), a rigid value system of discipline and honor that required them to live and die in the service of their lords.

If commanded, true bushi were expected to give their lives without hesitation. Any form of disgrace — cowardice, dishonor, defeat — reflected poorly on the lord and was reason enough for a bushi to commit suicide by seppuku, or ritual disembowelment. In return for this devotion, the lord provided protection, financial security, and social status — in short, a reason to live.

The bushi swore unwavering loyalty to their immediate masters in the chain of command. But this wasn’t always easy. Frequently, switched loyalties and shifting alliances forced the bushi to decide between obeying the daimyô (baron) or following their more immediate lord.

Although elegant and refined in appearance, Japanese castles were used as military installments. The wood used in their construction allowed these castles to withstand Japan’s many earthquakes but made them susceptible to fire at the same time.

Shôgun Might

The daimyô reported to the shôgun, more out of political and military necessity than out of loyalty. The shôgun became the most dominant feudal lord by subduing the other daimyô and receiving from the emperor the impressive title “Barbarian-Quelling Generalissimo.” Not that the emperor wielded any sort of political power — the awesome military might of the shôgun often left the emperor little choice but to grant the title.

The shogunal rule of the bakufu, (tent government) began in earnest with the Kamakura period (1185-1333), when the Minamoto clan defeated its bitter rival, the Taira family.

When Mongol invaders tried to land in western Japan, they were repelled by the Kamakura bakufu — with the help of kamikaze, powerful storms thought to be of divine origin. Despite this seeming divine favor, though, the bakufu could not withstand the unstable political situation on the domestic front.

The Kinkakuji — or “Golden Pavilion” — was originally built as a villa for the third Ashikaga shogun, Yoshimitsu. Upon his death, the eye-catching structure became a Zen Buddhist temple — creating an unusual combination of extravagant decor and minimalist doctrine.

The next to ascend to power were the Ashikaga, who established the Muromachi Bakufu (1336-1573). The third Ashikaga shôgun, Yoshimitsu (1358-1408), was a patron of the arts and oversaw such cultural achievements as the construction of the picturesque Kinkakuji (Golden Pavilion) and the flowering of Nô drama as the classical theater of Japan. The greatest figure in Nô was Zeami Motokiyo (1363-1443), whose aesthetic and critical theories defined the genre and influenced subsequent performing arts.

The downfall of the Ashikaga came about with the rise of the first of three “Great Unifiers” who sought to consolidate power. Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582) was a minor daimyô who embarked on a ruthless campaign for control that culminated in the removal of the last Ashikaga shôgun.

Western Influence, Feudal Struggle

Japan was a land of mystery to foreign explorers such as the English and Dutch, as shown by this somewhat inaccurate 17th-century map.

It was under Nobunaga’s watch that Europeans first arrived in Japan, and he took full advantage of their presence. Part of his military success came from his use of firearms, brought to Japan by the Portuguese, which allowed him swift and complete dominance.

Nobunaga’s hostility toward Buddhism, which he expressed by burning countless monasteries and slaughtering monks, made him receptive to the influx of Jesuit missionaries from Spain and Portugal.

When Nobunaga’s tenure ended in betrayal and death, the next leader who rose from the ensuing chaos was Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598), one of Nobunaga’s loyal vassals. Urasenke FoundationThe Japanese tea ceremony, otherwise known as chadô, has very precise steps to follow. This participant demonstrates the correct way to hold a teacup; in her left hand while steadying it with her right.

Originally a peasant of humble origins, Hideyoshi surged through the ranks to become a leading general. His hunger for power knew no bounds. He organized two invasions of Korea (both failed) and schemed to make the Spanish Philippines, China, and even India part of his empire.

Hideyoshi’s obsession with complete control pushed him to execute Christian missionaries and even to order the great master of the tea ceremony, Sen no Rikyû (1522-91), to commit suicide for no apparent reason. But because of his peasant origins, Hideyoshi was never able to become shôgun, and instead, he became regent to the emperor.

After Hideyoshi’s death, another power struggle ensued, in which two factions battled over the realm. The side led by the powerful daimyô Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616) prevailed, and within a short time, the mighty Tokugawa Bakufu was established in Edo — now known as Tokyo. Centuries of strife were finally over; for the next 300 years, peace and order would rule the land.

| Tennô (Emperor) | The symbolic ruler of Japan descended from and representative of Shintô deities; during the feudal period, mostly a figurehead. |

| Shôgun (Generalissimo) | Head of bakufu military government, with the power to oversee national affairs; receives title from the emperor; usually the strongest daimyô. |

| Daimyô (Lord of a domain) | Powerful warlord with control over territories of varying size; strength frequently determined by the domain’s kokudaka (tax based upon rice production). |

| Kerai or Gokenin (Vassal) | Loyal to the daimyô; receives fiefs or rice stipends from the daimyô; some comparable in strength to lesser daimyô. |

| Bugyô (Magistrate) | Appointed by the shôgun to oversee a specific government post (e.g., finance, construction), a large city (e.g., Edo, Nagasaki), or a region. |

| Daikan (Intendant) | Appointed by the daimyô or the shôgun to collect taxes and oversee the administration of local regions. |

| Shôya (Village headman) | Commoner was appointed by the daimyô or the shôgun to represent the bakufu at the village level. |

Major Empires of the Americas

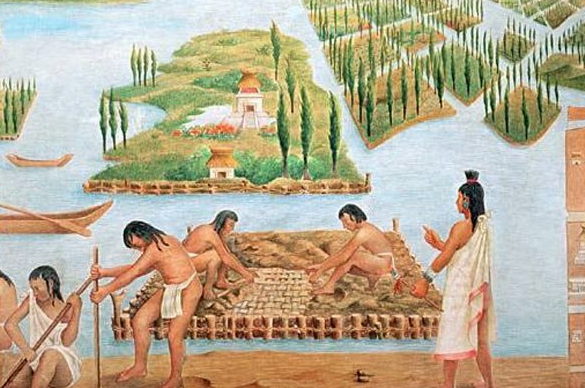

The Maya and Aztecs each dominated a region of Mesoamerica between 250 CE and 1550 CE. The Maya thrived in the rainforest of the Yucatan peninsula. Largely a kingdom of city-states that worked for mutual benefit, the Maya were able to build large temples, cities, and trade networks. Because of internal conflict and lack of food, the Maya empire collapsed around 900 CE. Before they collapsed, the Maya thrived, building a famous accurate calendar, a complex writing system, and pyramids that rival those of the Middle East. The Aztec Empire came years after the collapse of the Maya and occupied modern-day Mexico City and south. Their capital, Tenochtitlan, is where Mexico City is today. The city was enormous, housing nearly 200,000 people at a time when London had 50,000! The Aztecs built a series of great pyramids in their city, demonstrating their power and authority. The amazing part of this city is that it was built on Lake Texcoco. Aztecs would build chinampas, or floating gardens, in the lake to grow a bounty of food. These chinampas would be filled in over time, creating a larger and larger city.

The Aztecs practiced human sacrifice. Many of the temples in Tenochtitlan were used for these rituals. The people sacrificed were either captured in battle or were tributes given to the Aztecs by neighboring city-states that did not want to be attacked. These prisoners and tributes were often sacrificed to the sun god, Huitzilopochtli.

This process of human sacrifice was both part of their polytheistic religion and part of the political rule of the region. The Aztecs were very militaristic, had a thriving merchant class, and promoted education for many of its men.

The Incan Empire thrived around the same time as the Aztecs. They dominated a north to south region along the Andes Mountains in South America. They had a lot of clear contrasts with the Aztecs:

- They were much more of a united monarchy, while the Aztecs were largely a city-state empire controlled by Tenochtitlan.

- While the Aztecs sacrificed humans, the Inca sacrificed llamas.

- While the Aztecs had a vast trade network, the Inca believed in state-led economy.

- The Aztecs had city-states pay a tribute in humans to Tenochtitlan, while the Inca required a labor tax called mit’a. In this system, for example, the numerous roads that led to the capital of Cuzco were built by Incans who would work for about 1-2 years. They were not slaves, rather they paid their tax, or mit’a, with labor instead of money.

- While the Aztecs never formed a written language, the Inca created a system of knotted strings used to record numerical information called quipu.

A quipu usually consisted of cotton or camelid fiber strings. The Inca people used them for collecting data and keeping records, monitoring tax obligations, properly collecting census records, calendrical information, and for military organization. The cords stored numeric and other values encoded as knots, often in a base ten positional system. A quipu could have only a few or thousands of cords.

Continuities in the Americas after 1200 CE

Both the Aztec and Inca were animists and polytheists. Animism is a religious belief that objects and weather possess a distinct spiritual essence. This is why they both have sun gods (Huitzilopochtli and Inti). Polytheism means the belief in many gods: both the Aztecs and Inca had hundreds of gods.

- Chinampa: A form of Mesoamerican agriculture in which farmers cultivated crops in rectangular plots of land on lake beds; hosted corns, beans, chilis, squash, tomatoes, and more; provided up to seven harvests per year.

- Mit’a: A mandatory public service system in the Inca Empire requiring all people below the age of 50 to serve for two months out of the year; not to be confused with the mita, a forced labor system practiced by conquistadors in the former Inca Empire.