REVOLUTIONS

The Enlightenment

In the late eighteenth century, many people changed their minds about what made authority legitimate. Rather than basing political authority on divine right, some advocated new ideas about how the right to rule was bestowed. Many Enlightenment thinkers wanted broader participation in government and leaders who were more responsive to their people. This led to rebellions and independence movements against existing governments and the formation of new nations around the world. No longer content to be subjects of a king, new forms of group identity were formed around concepts such as culture, religion, shared history, and race. Colonized people developed identities separate from the European societies from which they emerged.

The rise and diffusion of Enlightenment thought that questioned established traditions in all areas of life often preceded the revolutions and rebellions against existing governments.

During the previous era (1450-1750) Europeans grew more willing to challenge established authorities on matters of culture, science, and religion. Borrowing the methods of science, the new ways of understanding the world began with one’s direct observations or experience, organizing the data of that experience, and only then evaluating political and social life. In a movement known as the Enlightenment, European intellectuals applied these methods to human relationships around them. They did not hesitate to question assumptions about government and society that had gone unquestioned for centuries. Dismissing all inherited beliefs about social class and religion, they began from direct experience and asked why things had to be the way they were.

Since the Middle Ages, religion formed the basis of almost every aspect of life in Europe. The Church sanctioned a hierarchical class system, supported the divine right of kings, and claimed to be the supreme authority on all knowledge claims. It did so by claiming to be the custodians of divine revelations which formed the basis of all that was true and were taken without question. During the Enlightenment, thinkers doubted the church’s claim to possess a source of divinely revealed absolute truth. Instead, they emphasized the capacity of human reason and experience to arrive at knowledge. They despised all dogma–the belief in propositions given by authorities that are not open to being challenged or examined for one’s self–and waged war against intolerance. In this regard, the most prominent figure is the French philosopher Voltaire. After wars of religion and the intolerance Catholics and Protestants demonstrated toward each other, Voltaire sought to destroy dogma and struggle against the power of the Catholic Church in European society.

The most profound influence of the Enlightenment was in political thought. New and radical ideas emanated from philosophers that challenged accepted notions of power. The English philosopher John Locke believed that all knowledge arises through experience, a belief that implies that experience rather than birth makes individuals who they are, thus calling into question the basis for the class system of Europe. He went on to argue that every individual has inalienable rights–rights that cannot be taken away without a grievous violation of natural law. For Locke, the most fundamental inalienable rights were life, liberty, and the right to own property.

The French philosopher Rousseau argued that the relationship between a government and its people was similar to a contract. This assumes that both parties are on equal footing and either side could violate the contract. Another English philosopher named Thomas Hobbes said that the only legitimate role of a government was to protect people from each other and anything beyond that was oppressive.

The French philosopher Montesquieu also argued for a limited government. He believed the best way to limit the power of a government was to divide its most fundamental powers–the power to make laws, execute laws, and interpret laws in specific instances– into three distinct and separate locations of government. This had a strong influence on the American system of dividing government into legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government with checks and balances between them. The net effect of all these philosophers was to deny the legitimacy of a government with absolute power supported by religion rather than the general will of the people.

The philosophers of the Enlightenment used the same assumptions about knowledge as the Scientific Revolution but used methods to change how life was lived.

The philosophies of the Enlightenment influenced several important political documents that were used to challenge traditional forms of political authority and call for radical changes in society and independence from political regimes.

- The Declaration of Independence The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789 is a fundamental document of the French Revolution and in the history of human rights written by Thomas Jefferson, the Declaration of Independence set forth a justification for the independence of Britain’s colonies in North America by claiming the actions of the English government violated the inalienable rights of the colonists as British subjects. It evoked John Locke’s ideas of the contractual relationship between a government and its people and made the case that King George III had overstepped his legitimate political power thus giving the colonists the right to separate from England. See the text of the Declaration of Independence HERE.

- The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen The Declaration of the Rights of Man was a product of the French Revolution. It was drafted by Lafayette, who was instrumental in the American Independence movement. This document proclaims the rights of all humans, regardless of social status. It effectively tore down the rights and privileges of the feudal class system and claimed that its concept of social equality and liberty was true of all people at all times and in all places. As an abstract declaration of rights for all people, it claimed universal and abstract liberty and was a permanent gain of the French Revolution. See the text of the Declaration of the Rights of Man HERE.

- Letter From Jamaica This is another document motivated by the political ideas of the Enlightenment. Written by Simon Bolivar in 1815, it justifies Spanish America’s independence from Spain. The document outlines the grievance the colonies have against Spain and speculates about the future of Latin America. Bolivar repeats his conviction that unity, rather than a US-style confederation, is necessary for the states of northern South America. See the English translation of the text HERE.

All of these Enlightenment-inspired documents imply a radically different arrangement of society than what was practiced at the time. For most of human history, varying levels of rights and privileges were assigned to groups in society rather than to individuals. Such groups were differentiated hierarchically by caste, race, religion, ownership of land, or some other criteria, and laws were different for each of them; inequality between groups was taken as a given. Enlightenment thought explicitly contradicted these assumptions. Lifting group designations completely, at least in theory, society was viewed as a collection of individuals who deserved to be treated in a uniform fashion. This new concept of individuality and universal rights initiated struggles to bring equality to women, dissolve feudal class systems, emancipate slaves, and expand suffrage to a wider range of people. However, social reform was not without challenges. The mulattoes in Haiti who claimed equality with the Creoles did not think for a moment that those same rights belonged to slaves; landowning planters fought the emancipation of serfs and other groups of coerced laborers; and in Europe, Pope Pious IX referred to universal suffrage as a “horrible plague which affected human society.”

The Enlightenment (Age of Reason) was a revolution in thought in Europe and North America from the late 17th century to the late 18th century. The Enlightenment involved new approaches in philosophy, science, and politics. Above all, the human capacity for reason was championed as the tool by which our knowledge could be extended, individual liberty maintained, and happiness secured.

Origins of the Enlightenment

The Enlightenment usually dates from the last quarter of the 17th century to the last quarter of the 18th century. During the Renaissance (1400-1600), when intellectuals and artists looked back to antiquity for inspiration, there arose the humanist movement, which stressed the promotion of civic virtue, that is, realizing a person’s full potential both for their own good and for the good of the society in which they live. The ideas of the Enlightenment flourished from these roots and blossomed thanks to events like the Protestant Reformation (1517-1648), which diminished the traditional power of the Christian Church in everyday life. Most enlightened thinkers did not want to replace the Church, but they did want greater religious freedom and toleration.

The Enlightenment derives its name ‘light’ from the contrast to what was then seen as the ‘darkness’ of the Middle Ages. We now know that the medieval period was perhaps not quite as ‘dark’ as once thought, but the essential fact remains that religion, superstition, and deference to authority did permeate that period of human existence before philosophers began to challenge these concepts in the 17th century. It was no longer possible to simply accept received wisdom as truth just because it had been unchallenged for centuries.

In this new atmosphere of relative intellectual freedom, reason challenged accepted beliefs. Just like the practical experiments scientists were conducting in the Scientific Revolution to discover the laws of nature, so, too, philosophers were keen to apply reason to age-old problems of how we should live together in societies, how we can be virtuous, what is the best form of government, and what constitutes happiness. This was a battle of reason against emotion, superstition, and fear; its principal weapons were optimism for a better world and both the freedom and ability to question absolutely everything. Not for nothing were the new enlightened philosophers also called ‘free-thinkers’.

Pre-Enlightenment Thinkers

The Enlightenment was driven forward by philosophers, although given that many were also writers of non-philosophical works or even dabbled in politics, they might be better described today as intellectuals. These thinkers challenged accepted thought and, it is important to stress, each other, since there was never any consensus as to the answers to the questions everyone was trying to answer. What is sure is this process of examining and building knowledge was a long one, with different strands in different places. With hindsight, we can reconstruct the chain of ideas we collectively call the Enlightenment, but the participants at that time were aware that they were involved in a new movement of thought.

There is a group of thinkers who are often called ‘pre-Enlightenment’ philosophers since they established some of the key foundations upon which the Enlightenment was built. This group includes Francis Bacon (1561-1626), Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), René Descartes (1596-1650), Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677), and John Locke (1632-1704).

Bacon stressed the need for a new combined method of empirical experimentation (i.e. observation and experience) and shared data collection so that humanity might finally discover all of nature’s secrets and improve itself. This approach was adopted by many enlightened philosophers. Bacon’s thoughts on the need to test our knowledge to see if it is actually true and his belief that we could build a better world if we all applied ourselves were also influential.

Hobbes, an English politician and thinker, proposed the idea of a state of nature, a brutish existence before we got together into societies. Hobbes believed that citizens must sacrifice some liberties in order to gain the security of society, and they do this when they form a social contract between themselves, that is, a collective promise to abide by certain rules of behavior. He also believed, because of his pessimistic view of human nature, where people act entirely out of self-interest, that a very strong political authority was required, his Leviathan, named after the biblical monster. These ideas and Hobbes’ attempt to disentangle philosophy, morality, and politics from religion would all inspire Enlightenment thinkers, either in support or in providing alternative models.

Descartes, a French rationalist philosopher, proposed that all knowledge must be subjected to doubt because our senses are unreliable, we may be dreaming, or we may be living in a deception created by an evil demon. Descartes’ conclusion of applying doubt to everything is his founding principle of indubitable truth Cogito, ergo sum (“I think, therefore I am”). From Decartes’ ideas came Cartesianism and the position that the mind and body (or matter) are two distinct things but, in some way that thinkers had yet to determine, they interact with each other. While some critics point out that Descartes’ hunting down of doubts can lead to absurdities and total skepticism, his strategy has importance for the Enlightenment since it demonstrates the value of questioning everything and not taking at face value knowledge we have inherited from previous generations – knowledge that may, in fact, turn out to be not knowledge at all but only belief.

The Dutchman Spinoza attacked superstition and challenged the traditional role of God in human affairs, suggesting God does not interfere in our everyday lives. Combining rationalism and metaphysics, Spinoza was greatly interested in science and believed that by using our reason and studying nature we could come to better know ourselves and the divine. He also called for greater religious toleration.

The Englishman Locke proposed that there should be limits on state power in order to guarantee certain liberties, especially the right to hold property, which he considered a natural right (i.e. it is not given by a government or law code). Locke’s perfect state has a separation of powers, and the government can only operate if it has the consent of the people. Further, citizens can overthrow a government if it does not perform its role of protecting their rights. Locke believed humans can work together for a common good. He believed that individuals are more important than institutions like absolute monarchs and the Church. He believed that all citizens are equal and the state should educate its citizens to be reasoned and tolerant citizens. More than any other thinker, perhaps, Locke’s ideas not only inspired other thinkers but also influenced real-world affairs.

There were many other thinkers that influenced the Enlightenment, but space precludes discussion of them here; men like the German polymath Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716), who believed that all knowledge was interconnected. In short, a whole body of international thinkers had already come up with the essential playing cards of the Enlightenment game before it had even started. Later philosophers now reshuffled these, selected some, and rejected others in their search for the winning hand of just how humans should live and how knowledge should be acquired.

10 Key Enlightenment Thinkers

Having set the foundation, then, a new wave of thinkers set about building a new edifice of Western knowledge. Disagreeing just as often they agreed with each other, all of the thinkers had the common objective of finding a better world to live in.

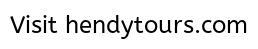

One of the first texts of the Enlightenment proper was the 1687 Principia Mathematica by Isaac Newton (1642-1727). Newton’s book is in many ways a culmination of the Scientific Revolution, and it presents the view that the world around us can be understood, and the best tool for that purpose is science, in particular, mathematics. In his discovery of the force of gravity (and others besides), Newton showed that empiricism and deduction were the best methods to increase knowledge. Philosophers took this approach in their own work. Newton also showed that there was harmony and order in nature, which was something that philosophers sought to recreate in human society.

The French philosophe Montesquieu (1689-1757) was mostly concerned with avoiding authoritarian government. Going beyond Locke, he researched the history of politics – essentially founding political science – and famously articulated a separation of powers between the executive, legislative, and judiciary. He is another thinker who advocates the protection of individual liberty through laws, non-government interference, and toleration. To give an idea of the battle with the Establishment many enlightened thinkers had to face, Montesquieu’s book The Spirit of the Laws was put on the Catholic Church’s Index of Prohibited Books in 1751.

The French author Voltaire (1694-1778) “more than any other represented the Enlightenment to his contemporaries” (Chisick, 430). Less an original philosopher and more a destroyer of the old attitudes, Voltaire was critical of the power of the Catholic Church, he called for more individual liberty and religious toleration, and championed our power of reason and innate capacity for moral behaviour. Voltaire also chastised philosophers for not coming up with practical solutions to society’s problems.

David Hume (1711-1776) was a Scottish philosopher, who presented a positive view of human nature – we all possess a capacity for sympathy and a natural moral sense – but a sceptical view of religion’s usefulness. Hume believed knowledge comes only from experience and observation but also acknowledged there are some things we can never know such as, why is there evil in the world? Hume expanded the notion of reason to include emotion.

The Swiss thinker Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) contributed with his mixing of Hobbes and Locke in stating that humans in a state of nature are free, equal, and have two basic instincts: a sense of self-preservation and a pity for others. The people must gather in a community based on consent and with the ultimate objective of that society being the common good. For Rousseau, the general will is a compromise where individuals sacrifice complete liberty to achieve the next best option: a restriction on liberty in order to avoid a situation of no liberty at all. Whatever the general will turns out to be, that is the right one. Rousseau does recognise the need for a system of laws and strong government to guide the general will of the people when it might inadvertently err and to protect property, for him, an unfortunate creation of society. Rousseau was also concerned with ridding society of its obvious inequalities and injustices by having the state encourage its citizens through education to adopt a less self-interested approach to community life.

The thoughts of the Frenchman Denis Diderot (1713-1784) may be summarised as a humanistic belief in individual autonomy and the positive use of modern, non-religious, and, if possible, scientific arguments and methods to challenge age-old knowledge based on faith and superstition alone. Diderot was editor of the multivolume Encyclopedia, often described as the ‘Bible of the Enlightenment’ and summarised by N. Hampson as “an anthology of ‘enlightened’ opinions on politics, philosophy, and religion” (86). Diderot spent time advising both Catherine the Great (empress regent of Russia, 1762-1796) and Frederick the Great in Prussia (l. 1712-1786), examples of so-called ‘Enlightened despots’.

Adam Smith (1723-1790) was a Scottish philosopher and economist. He believed that economics is a science and follows certain laws, what he called the ‘Invisible Hand’. These laws, like any laws of nature, can be discovered through the use of reason. Smith called for free trade and limited interference in markets by governments, for which he is seen as the founder of liberal economics. A. Gottlieb describes Smith’s The Wealth of Nations as “the founding text of modern economics” (198).

The German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) challenged the dominance of empiricism and rationalism in Enlightenment thought as he believed that some knowledge must be independent of sensation, examples given include our concepts of space and time. These things are a priori knowledge, things that we can think about without ever experiencing them directly. Consequently, Kant shifted the focus of philosophy to an examination of general concepts and categories. In ethics, Kant stated that moral worth comes from a person’s intentions and not from the results of their actions, which could be accidental. Good actions spring from following rules without exceptions like “never tell lies”, what he called categorical imperatives. Kant also stressed the need for toleration, education, and cooperation between nations.

Edmund Burke (1729-1797) stated that any nation and its institutions, including religious ones, were a product of a rich and long history, and so one particular generation should not simply cast away such time-tested guardians of our safety and liberty. Burke also thought that intuition and imagination were just as important tools as reason in understanding our world.

Thomas Paine (1737-1809), in his pamphlet Common Sense, famously called for the American colonies to rebel against British rule. Paine denounced slavery, was opposed to any form of privilege, believed all men are equal and should have the right to vote, and he called for a system of progressive taxation that could fund a fairer society.

Here we have considered only ten enlightened thinkers, but there were, of course, many more, but, unfortunately, space precludes their mention. The trend to apply enlightened thought to practical everyday problems was continued. Cesare Beccaria (1738-1794) called for prison reform and the end of excessive punishments for criminals. Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797) called for equal education opportunities for men and women and stressed the benefits to society of improving the situation of women. Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) offered a way to measure the success of new laws with his utilitarianism and its “greatest happiness of the greatest number principle”. Thinking about a better world had been the priority of the Enlightenment, but as the 18th century wore on, actually making one became the new priority.

A Great Mixing of Ideas

For ideas to spread and take root, there needed to be interaction between intellectuals, and this was achieved (beyond merely physically visiting each other) by several new means. The printing press allowed not only books to be distributed relatively cheaply but also treatises, pamphlets, and magazines. Never before had so much paper been passed across Europe. Ideas, and perhaps even more importantly, critical reaction to those ideas, and so the stimulus for yet more ideas, could be spread faster than ever before.

Another means for intellectuals to interact was the rise of academies and societies, where papers were published in in-house magazines, and meetings and debates were held. People also met in coffee houses to discuss new ideas. Yet another means of spreading ideas was the salon, particularly in Paris, although soon the idea caught on everywhere. These salons, so often managed by women, further aided the transmission of ideas not only between intellectuals but also different sections of society. For the first time, perhaps, philosophers, artists, politicians, and business people were able to meet together informally. Further, there was even some mixing of different levels of society in salons since the intellectuals and artistic creators could now meet aristocrats and those with great wealth, a meeting that often led to patronage, and so yet more ideas could be created.

The Impact of the Enlightenment

A key idea of enlightened thinkers was the belief that human existence could be improved through human endeavour. Developments in science and technology as well as progressive thinking in political philosophy meant that a better standard of living could be achieved for everyone. Reforms were championed that reduced society’s inequalities and diminished the impact of such negative but all-too-present phenomena as famine, disease, and poverty. Reformers called for real change in education so that more young people could attend school and become better citizens by developing their natural ability to reason. Just as individuals were to be left to pursue their own liberty and happiness in the new politics of liberalism, there developed the idea of laissez-faire economics, that is, minimising government interference to let the economy develop as the markets dictated it should. Modern liberal democracies then are based on the Enlightenment idea that some areas of life are no business of the state, a marked difference to societies of the Middle Ages.

To these general consequences of the Enlightenment, there can be added definite practical ones. As the Enlightenment specialist N. Hampson notes, the danger of studying the Enlightenment only in intellectual terms can lead to the conclusion that “the Enlightenment was everything in general and nothing in particular” (Cameron, 296). Some practical particulars include the end of the persecution of heretics, no more witches being burnt at the stake, serfdom coming to its final stage, and torture being removed from judicial processes. There were powerful movements to end slavery and the death penalty. The Church was formally separated from the state in some places, notably France. More universities and libraries were founded. Greater fairness was achieved in electoral systems.

The impact of the progress in science would be seen in the British Industrial Revolution (1760-1840) and its counterparts across the world. Many enlightened thinkers also foresaw the darker side of ‘progress’, such as an unrestrained individualism opposed to the common good and minority-controlled technological development that alienated large groups of people and destroyed the environment.

It was not just the intellectuals who believed they could shape a better future. It took a long time for the high ideas of intellectuals to filter down to the lower classes, but descend they eventually did. Ordinary people of all classes now considered taking direct action to improve their lot in life and the political systems in which they lived. The two clearest examples of this action for a better world are the French Revolution and the American Revolutionary War. Revolutionaries in both events were inspired by and frequently quoted the works of enlightened philosophers; their revolutionary documents like the French Bill of Rights and the US Declaration of Independence were replete with the language these philosophers were using such as “inalienable rights” and “pursuit of happiness”.

Criticisms of the Enlightenment

In some areas like the arts, there was a reaction to the Enlightenment and the new dominance of reason. This reaction was seen most clearly in the movement we call Romanticism (1775-1830), where, in literature and art, emphasis was given to new forms and modes of emotional and spontaneous expression.

Other critics of the Enlightenment lament its contradictory results such as a possible overemphasis on individuals and yet also a strong state. Critics point to the rejection of cultural traditions, the reduction in value of faith and religious beliefs, that economic, scientific, and technological ‘progress’ is, in fact, only ‘regression’ in terms of our humanity, and that the Eurocentric philosophers were ignorant of what makes humans different in different places (or even the same place). In short, the Enlightenment has been blamed for all the ills of modernity, whether it be the Holocaust or the destruction of the Brazilian rainforest. One might counterargue, and plenty of historians have, that such blanket criticisms can only be made against the Enlightenment if one takes it as an entirely homogenous collection of ideas, something this article hopefully discourages.

Into the 21st century, the achievements of the Enlightenment, particularly liberty, freedom of thought, and toleration are still in existence in many places, but certainly not everywhere. As the historian H. Chisick points out these freedoms are not immune to ever-present threats like racism, political extremism, and religious fanaticism:

“Apparently, the key values of the Enlightenment are not acquired once and for all. Rather, they must be appropriated by each generation and each culture in turn, or they will be submerged and lost.”

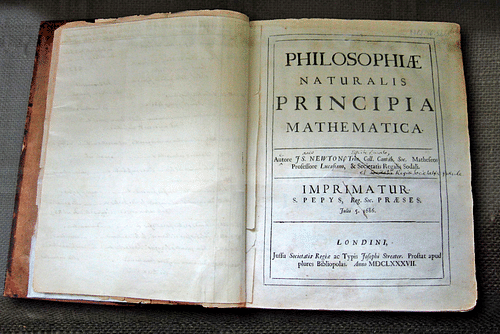

The American Revolution

If the Enlightenment thinkers all got in a room together and said “What is the best representation of our writings, goals, and ideals?” They would surely have answered, “The American Revolution“. The first state to gain independence in the New World, the USA was built on the Enlightenment. It’s written into our Declaration, Constitution, and Bill of Rights. We the People stood up for our rights and fought a war to gain them. Locke, Montesquieu, and the boys would certainly be proud of how far their ideas have taken us. For most of you, APUSH (AP United States History) will cover this in greater detail next year. For now, you should view the American Revolution as a key part of the 1750-1900 AP World era in which colonies in the Western Hemisphere gain their independence.

Key Vocabulary Terms for American Independence

- ENLIGHTENMENT

- STAMP ACT

- TAXATION WITHOUT REPRESENTATION

- DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE

- THOMAS JEFFERSON

- GEORGE WASHINGTON

- BATTLE OF SARATOGA

- BATTLE OF YORKTOWN

- CONSTITUTION

- BILL OF RIGHTS

American Revolution Timeline

1775-1783

“The Surrender of Lord Cornwallis” is an oil painting by John Trumbull. The painting was completed in 1820, and hangs in the rotunda of the United States Capitol in Washington, D. C.

Explore the timeline of the American Revolution and learn about the important events and battles that happened throughout this period of American history – from the Battles of Lexington and Concord to the signing of the Treaty of Paris. View the War of 1812 and Civil War timelines.

- May 28 – The French and Indian War begins

- July 10 – Albany Plan of Union—Benjamin Franklin proposes a single government for the colonies

1763

- February 10 – The Treaty of Paris ends the French and Indian War. The English drive the French from North America, and the English national debt soars

- October 7 – Proclamation of 1763—King George III banned colonists from settling beyond the Appalachian mountains

1764

- April 5 – Sugar Act—Smugglers could be tried in Admiralty Courts, without the benefit of a jury

1765

- March 22 – Stamp Act—Tax on paper goods and legal documents

- March 24 – Quartering Act—Colonies must provide housing and food for British troops

- March 29 – Virginia House of Burgesses passes the Virginia Resolves, 7 resolutions that challenge the legality of the Stamp Act

- October 7-25 – Stamp Act Congress meets in Philadelphia to discuss the crisis

1766

- March 18 – Parliament repeals the Stamp Act and passes the Declaratory Act, which reiterates Parliament’s authority over the colonies

1768

- February 11 – Massachusetts Assembly issues Massachusetts Circular Letter, denouncing Townsend Acts

- August 1 – Boston Non-Importation Agreement—Boston merchants agree to not import British goods, or sell to Britain

1770

- January 19 – Golden Hill Riot, NY

- March 5 – Boston Massacre

1772

- June 9 – Gaspée Affair—A British ship patrolling for smugglers runs aground in Rhode Island and a local mob burns it; the mob is then accused of treason

1773

- May 10 – Tea Act—An attempt by Parliament to undercut smugglers by reducing the price of tea to the colonies

- December 16 – Boston Tea Party

1774

- March 31 – Boston Port Act— Parliament closes the city’s port in response to the Tea Party.

- May 20 – Administration of Justice Act and Massachusetts Government Act, two of the so-called Intolerable Acts, further anger colonists

- June 2 – Quartering Act is amended

- September 5–October 26 – First Continental Congress—Carpenter’s Hall, Philadelphia

- March 23 – Patrick Henry’s “Liberty or Death” speech, Richmond, VA

- April 18 – Revere and Dawes Ride

- April 19 – Battles of Lexington and Concord, MA

- May 10 – Ethan Allen and Green Mountain Boys seize Fort Ticonderoga, Second Continental Congress meets

- June 15 – George Washington appointed commander-in-chief

- June 17 – Battle of Bunker Hill

- July 3 – George Washington assumes command of the Army outside Boston

- July 5 – Congress approves the Olive Branch Petition, a final attempt to avoid war with Britain

- October 13 – The U.S. Navy is established

- November 19-21 – First Siege of Ninety Six, SC

- November 13 – Americans take Montreal

- December 9 – Battle of Great Bridge, VA

- December 22 – Battle of Great Canebreak, SC

- December 23-30 – Snow Campaign, SC

- December 30-Jan 1 – Battle of Quebec

- January 10 – Thomas Paine publishes Common Sense

- February 27 – Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge, NC

- March 3 – Continental Navy captures New Providence Island, Bahamas

- March 17 – British evacuate Boston

- April 12 – Halifax Resolves, NC—First colony to authorize its delegates to vote for independence

- June 7 – Lee Resolution: Richard Henry Lee proposes independence to the Second Continental Congress

- June 28 – Battle of Sullivan’s Island, SC

- July 1 – Cherokee attack the southern frontier

- July 4 – Congress adopts the Declaration of Independence

- August 27 – Battle of Brooklyn, NY

- September 15 – British occupy Manhattan

- September 16 – Battle of Harlem Heights, NY

- September 22 – British execute Nathan Hale, a soldier in the Continental Army

- October 11 – Battle of Valcour Island, Lake Champlain

- October 28 – Battle of White Plains, NY

- November 16 – Battle of Fort Washington, NY

- November 20 – British capture Fort Lee, NJ

- December 23 – Thomas Paine publishes The American Crisis

- December 26 – Battle of Trenton, NJ

- January 3 – Battle of Princeton, NJ

- January 6 – May 28 – Continental Army winters at Morristown, NJ

- April 27 – Battle at Ridgefield, CT

- June 14 – Flag Resolution– Congress declared “That the flag of the thirteen United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field”

- July 5 – British capture Fort Ticonderoga

- August 6 – Battle of Oriskany, NY

- August 16 – Battle of Bennington, VT (Walloomsac, NY)

- September 11 – Battle of Brandywine, PA

- September 19 – Battle of Saratoga, NY (Freeman’s Farm)

- September 20-21 – Battle of Paoli, PA

- September 26 – British take Philadelphia

- October 4 – Battle of Germantown, PA

- October 7 – Battle of Saratoga, NY (Bemis Heights)

- October 17 – British surrender at Saratoga, NY

- October 22 – Battle of Fort Mercer, NJ

- November 16 – British capture Fort Mifflin, PA

- December 5–7 – Battle of White Marsh, PA

- December 19 – Washington and his army winter in Valley Forge

- February 6 – The United States and France become allies

- February 7 – British General William Howe replaced by Henry Clinton

- May 20 – Battle of Barren Hill, PA

- June 18 – British abandon Philadelphia, Continental Army marches out of Valley Forge

- June 28 – Battle of Monmouth, NJ

- July 4 – George Rogers Clark captures Kaskaskia, in modern Illinois

- July 29–August 31 – French and American forces besiege Newport, RI

- December 29 – British capture Savannah, GA

- February 3 – Battle of Port Royal Island, SC

- February 14 – Battle of Kettle Creek, GA

- February 23–24 – George Rogers Clark captures Vincennes, in modern Indiana

- March 3 – Battle of Brier Creek, GA

- June 18 – Sullivan expedition attacks Indian villages in NY

- June 20 – Battle of Stono River, SC

- June 21 – Spain declares war on Great Britain

- July 7 – British burn Fairfield, CT

- July 11 – British burn Norwalk, CT

- July 16 – Americans capture Stony Point, NY

- July 24 – August 14 – Penobscot Expedition (Castine, ME)

- July 28 – Battle of Fort Freeland, PA

- August 19 – Battle of Paulus Hook, NJ

- August 29 – Battle of Newtown, NY

- September 16 – October 19 – American/French effort to retake Savannah fails

- September 23 – John Paul Jones and the USS Bonhomme Richard capture HMS Serapis near English coast

- November – Washington’s Main Army begins camping at Morristown, NJ

- January 28 – Fort Nashborough established (now Nashville, TN)

- March 14 – Spanish capture Mobile

- May 12 – British capture Charleston, SC

- May 25 – Mutiny of Connecticut regiments at Morristown, NJ

- May 26 – Battle at St. Louis, now in Missouri

- May 29 – Battle of Waxhaws, SC

- June 20 – Battle of Ramseur’s Mill, NC

- June 23 – Washington’s Main Army leaves their winter camps at Morristown, NJ

- July 11 – French troops arrive at Newport, RI

- August 6 – Battle of Hanging Rock, SC

- August 16 – Battle of Camden, SC

- August 19 – Battle of Musgrove Mill, SC

- September 23 – British officer John Andre arrested for spying

- October 7 – Battle of Kings Mountain, SC

- October 14 – Gen. Nathanael Greene named commander of the southern Continental Army

- October 18 – British occupy Wilmington, NC

- January 17 – Battle of Cowpens, SC

- February 1 – Battle of Cowan’s Ford, NC

- February 12 – Spanish forces take Fort St. Joseph, now Miles, MI

- March 2 – Articles of Confederation adopted; Battle of Clapp’s Mill, NC

- March 6 – Battle of Weitzel’s Mill, NC

- March 15 – Battle of Guilford Courthouse, NC

- April 25 – Battle of Hobkirk Hill, SC

- May 9 – Spanish capture Pensacola

- May 15 – Battle of Fort Granby, SC

- May 22–June 18 – Siege of Ninety Six, SC

- June 6 – Americans retake Augusta, GA

- July 6 – Battle at Green Spring, VA

- August 28 – Battle of Elizabethtown, NC

- September 5 – Battle of the Capes, Chesapeake Bay

- September 8 – Battle of Eutaw Springs, SC

- September 28 – October 19 – Siege of Yorktown, VA

- October 19 – General Cornwallis officially surrenders at Yorktown, VA

- March 8—9 – Indians attacked by militia at Gnadenhutten, in modern OH

- March 20 – Lord North resigns as Prime Minister of Great Britain

- April 19 – Netherlands recognizes American independence

- May 8 – American and Spanish forces capture Nassau, Bahamas

- July 11 – British evacuate Savannah, GA

- July 13 – British/Indian raid on Hannahstown, PA

- August 7 – Washington establishes the Badge of Military Merit, now known as the Purple Heart

- August 19 – Battle of Blue Licks, KY

- November 4 – Encounter at John’s Ferry, SC

- November 10 – George Rogers Clark raids Chillicothe, modern OH

- November 30 – British and Americans sign preliminary Articles of Peace

- December 14 – British evacuate Charleston, SC

- March 15 – Washington addresses the Newburgh Conspiracy and discontent in the Continental Army, Newburgh, NY

- April 19 – Congress ratifies the preliminary peace treaty

- September 3 – US and Great Britain sign the Treaty of Paris

- November 25 – British evacuate New York City

- December 4 – Washington bids farewell to his officers in New York City

- December 23 – Washington resigns as commander in Annapolis, MD

Nationalism and Revolutions

Beginning in the eighteenth century, people around the world developed a new sense of commonality based on language, religion, social customs, and territory. These newly imagined national communities linked this identity with the borders of the state, while governments used this idea to unite diverse populations.

Since the dawn of human societies, people have been inclined to identify themselves as part of a group, whether it be a tribe or clan, Caliphate or kingdom. Enlightenment ideas, particularly those emanating from the French Revolution, created a modern way of establishing group identity. Previous identities usually centered around the leader who possessed some kind of mandate–religious or otherwise–to exercise authority over the people. Before the revolution in France, for example, people thought of themselves as subjects of the king who ruled by divine right. When they went to war, they marched for the monarch. However, after the French demoted–and then executed–their king during the Revolution, this concept of identity necessarily ended. They were no longer subjects of the king, but citizens of the nation of France. Nations are human constructs based on commonalities, usually language, ethnicity, territorial claims, religious bonds, or shared history, whether real or imagined. This cohesive force is called nationalism, and most nations seek to be politically autonomous on a specific territory (a nation-state). Thus it can be deadly to empires as it encourages different ethnic or religious groups to break away to form independent states. As a powerful force in uniting and motivating people, politicians can exploit nationalist feelings for their own objectives. At its worst, nationalism marginalizes groups of people who do not fit the ethnic or religious identity of the nation, which can lead to persecution and violence.

In order to understand how the French Revolution changed France, one must first understand the way France was under the Old Regime. Although Louis XIV had done a great deal to build a French nation, France still remained in many ways a patchwork of regions dominated by clerics and aristocrats who made up the First and Second Estates. Due in part to tax exemptions enjoyed by the privileged classes, France found itself in a major financial crisis in the late 1780s, forcing the monarchy to call a meeting of the Estates General. When the Estates General was convened in 1789, it was convened under antiquated rules that Third Estate delegates found to be offensive. The failure of the Estates General was a watershed event in the French Revolution, opening the door for changes that were far more radical than any that had been proposed by the Third Estate delegates in 1789.

After the failure of the Estates General, the National Assembly convened and began swiftly enacting liberal reforms. Following the Great Fear and the storming of the Bastille in the summer of 1789, the National Assembly passed the August 4 Decrees and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen. While the Declaration of the Rights of Man was heavily influenced by the classical liberal philosophy found in the writings of Thomas Jefferson and John Locke, it was also heavily influenced by the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose idea of the social contract subordinated individualism to the “general will” of the nation. When seen as a dialogue between Jefferson and Rousseau, the Declaration of the Rights of Man both articulates the goals of the liberal revolution of 1789 while also foreshadowing the radical revolution of 1792-1794.

Women and the French Revolution

While the French Revolution was not a feminist revolution, the upheaval it created had a hand in bringing about the modern feminist movement. In the 18th century, women were still barred from the public sphere and the Enlightenment did little to change this; in fact, Rousseau defended traditional views of women in his educational treatise, Emile.

The Radicalization of the French Revolution

Starting in 1791, the French Revolution began a period of radicalization, as the initial idea of a constitutional monarchy on the British model was abandoned in favor of a French Republic. The increasing influence of the Jacobin clubs led to the execution of Louis XVI and the election of the National Convention that would authorize the Reign of Terror.

The Reign of Terror

The Reign of Terror (1793-1794) was the most radical phase of the French Revolution and the most memorable in spite of its brevity. The National Convention and Robespierre presided over this short period when the blade of the guillotine severed heads on a regular basis.

The French Directory

After the Thermidorian Reaction and the fall of Robespierre, the bourgeoisie reasserted control and limited the participation of the radical Parisian mobs that had been so influential during the Reign of Terror. Executive authority was wielded by five directors, from which this period from 1794-1799 got its name.

Napoleon

In 1799, Napoleon overthrew the Directory and dominated French politics until his final overthrow and exile in 1815. Napoleon’s rule can be divided into the Consulate (1799-1804) and the French Empire (1804-1815). Some of his key political accomplishments were the Napoleonic Code, which gave France a uniform code of laws based on Roman Law, and the Concordat of 1801, which established Catholicism as the “majority religion” after a period of de-Christianization in the 1790s.

The Haitian Revolution

The French transported more Africans to Saint-Domingue (773,000) than to any other part of the French Caribbean, a clear indication of the explosive growth of the colony’s slave-based economy over the course of the eighteenth century. In this rapidly expanding colony, booming on the back of slave-grown sugar and coffee production, French slave owners worked Africans as intensively and as brutally as anywhere in the Americas. Perhaps not surprising, then, that Saint-Domingue was to prove fertile ground for the grievances of the enslaved, whose anger erupted with volcanic fury after the ideals and the turmoil of the French Revolution swept through French Caribbean colonies after 1789.

Though long ignored by many who study the Age of Revolutions, the Haitian Revolution stands out as the only instance in which enslaved people and free people of color fought and defeated the French, Spanish, and British to end slavery and the slave trade. This successful and complicated campaign for freedom and equality, begun in 1791, resulted in the creation of the second republic in the western hemisphere, an independent Republic of Haiti in 1804.

In addition to their own desire for freedom from the harsh realities of slavery in Saint-Domingue, enslaved people, and their allies were inspired by both the rhetoric of the American and French Revolutions. In fact, several hundred men of color had joined with royal French soldiers in the American Revolutionary War in 1779, only to return home to Saint-Domingue after the siege of Savanna, Georgia, disillusioned with the treatment they received from their own officers there. In a complex upheaval involving free people of color, radical whites, and enslaved men and women, revolutionaries in Saint-Domingue overthrew local slavery, defeated French, Spanish, and British forces sent to crush them, and ultimately founded a republic based on the ideals of the revolutions that had inspired them.

During the wars that comprised the revolution from 1791 to 1803, white planters fled Saint-Domingue to other islands in the Caribbean and to North America (mainly to Louisiana and South Carolina), taking with them their slaves and spreading horror stories of what had happened in the slave uprising. Their vivid stories, and the news from the revolt, admonished slaveholders everywhere that they could not make concessions to enslaved people, and that, given the chance, their slaves would revolt against them.

More on the topic here.

The United States and the Haitian Revolution, 1791–1804

The Haitian Revolution created the second independent country in the Americas after the United States became independent in 1783. U.S. political leaders, many of them slaveowners, reacted to the emergence of Haiti as a state borne out of a slave revolt with ambivalence, at times providing aid to put down the revolt, and, later in the revolution, providing support to Toussaint L’Ouverture’s forces. Due to these shifts in policy and domestic concerns, the United States would not officially recognize Haitian independence until 1862. The image to the right is Toussaint L’Ouverture holding a printed copy of the Haitian Constitution of 1801. (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

Prior to its independence, Haiti was a French colony known as St. Domingue. St. Domingue’s slave-based sugar and coffee industries had been fast-growing and successful, and by the 1760s it had become the most profitable colony in the Americas. With the economic growth, however, came increasing exploitation of the African slaves who made up the overwhelming majority of the population. Prior to and after U.S. independence, American merchants enjoyed a healthy trade with St. Domingue.

The French Revolution had a great impact on the colony. St. Domingue’s white minority split into Royalist and Revolutionary factions, while the mixed-race population campaigned for civil rights. Sensing an opportunity, the slaves of northern St. Domingue organized and planned a massive rebellion which began on August 22, 1791.

When news of the slave revolt broke out, American leaders rushed to provide support for the whites of St. Domingue. However, the situation became more complex when civil commissioners sent to St. Domingue by the French revolutionary government convinced one of the slave revolt leaders, Toussaint L’Ouverture, that the new French Government was committed to ending slavery. What followed over the next decade was a complex and multi-sided civil war in which Spanish and British forces also intervened.

The situation in St. Domingue put the Democratic-Republican party and its leader, Thomas Jefferson, in somewhat of a political dilemma. Jefferson believed strongly in the French Revolution and the ideals it promoted, but as a Virginia slaveholder popular among other Virginia slaveholders, Jefferson also feared the specter of slave revolt. When faced with the question of what the United States should do about the French colony of St. Domingue, Jefferson favored offering limited aid to suppress the revolt, but also suggested that the slaveowners should aim for a compromise similar to that Jamaican slaveholders made with communities of escaped slaves in 1739. Despite their numerous differences on other issues, Secretary of the Treasury and leader of the rival Federalist Party Alexander Hamilton largely agreed with Jefferson regarding Haiti policy.

The Haitian revolution came to North American shores in the form of a refugee crisis. In 1793, competing factions battled for control of the then-capital of St. Domingue, Cap-Français (now Cap-Haïtien.) The fighting and ensuing fire destroyed much of the capital, and refugees piled into ships anchored in the harbor. The French navy deposited the refugees in Norfolk, Virginia. Many refugees also settled in Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York. These refugees were predominantly white, though many had brought their slaves with them. The refugees became involved in émigré politics, hoping to influence U.S. foreign policy. Anxieties about their actions, along with those of European radicals also residing in the United States, led to the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts. The growing xenophobia, along with temporarily improved political stability in France and St. Domingue, convinced many of the refugees to return home.

The beginning of the Federalist administration of President John Adams signaled a change in policy. Adams was resolutely anti-slavery and felt no need to aid white forces in St. Domingue. He was also concerned that L’Ouverture would choose to pursue a policy of state-supported piracy like that of the Barbary States. Lastly, St. Domingue’s trade had partially rebounded, and Adams wished to preserve trade links with the colony. Consequently, Adams decided to provide aid to L’Ouverture against his British-supported rivals. This situation was complicated by the Quasi-War with France—L’Ouverture continued to insist that St. Domingue was a French colony even as he pursued an independent foreign policy.

Under President Thomas Jefferson’s presidency, the United States cut off aid to L’Ouverture and instead pursued a policy to isolate Haiti, fearing that the Haitian revolution would spread to the United States. These concerns were in fact unfounded, as the fledgling Haitian state was more concerned with its own survival than with exporting revolution. Nevertheless, Jefferson grew even more hostile after L’Ouverture’s successor, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, ordered the execution of whites remaining after the Napoleonic attempts to reconquer St. Domingue and reimpose slavery (French defeat led to the Louisiana Purchase.) Jefferson refused to recognize Haitian independence, a policy to which U.S. Federalists also acquiesced. Although France recognized Haitian independence in 1825, Haitians would have to wait until 1862 for the United States to recognize Haiti’s status as a sovereign, independent nation.

Latin American Revolutions

Political upheavals and independence movements shook the foundations of empire in the late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Atlantic World. The American, French, and Haitian revolutions brought forth new expressions of individual rights and freedom that began to influence similar actions in the colonies of Latin America. Check out Simón Bolívar.

The origins of the Latin American independence movements of the early 1800s might be traced to changes in imperial administration. After many years of semi-autonomous local rule and limited metropolitan intervention, new bureaucratic reforms in the eighteenth century caused some discomfort in the American colonies. Whatever problems these reforms caused were magnified by the French invasion of Spain and Portugal in 1808. Following Napoleon’s disruption of royal power, some Latin American colonies established their own governments. When the Spanish and Portuguese tried to reassert control, their colonies began to move toward independence. The role of slavery and enslaved people in these places would be crucial in defining and maintaining independence.

In Venezuela, for example, the 1811 constitution ended the slave trade, but enforced slavery and racial discrimination. Across South America, political and social actions toward independence gave enslaved people greater motivation and opportunities to work toward their own freedom. When rhetoric turned to warfare, free and enslaved people of African descent became important sources of manpower in revolutionary armies. As had been the custom throughout the revolutionary Atlantic, individual manumission was earned through military service.

The new independent states—places like Argentina, Peru, Colombia, and Venezuela—passed laws to end the slave trade. However, they acted less quickly on the issue of slavery, often legislating schemes for gradual emancipation. People of color who had not won immediate manumission had to fight against legal and social barriers to full freedom, sometimes for decades.

Emancipation Movements

Slavery and the slave trade were always controversial practices. While nearly all societies in the Atlantic world accepted slavery and unfreedom, the institution always faced some opposition. Even as early as the sixteenth century, some individuals (like Bartolomé de las Casas, for example) argued against enslavement on moral grounds. As slavery grew in economic and political significance, imperial and colonial powers faced powerful, organized pressure to support and maintain slavery. As a consequence, the different movements that advocated for the end of slavery and the end of the slave trade had to mobilize a variety of moral, legal, social, and political resources to be successful.

Emancipation movements generally evolved along two different lines: one opposing the slave trade and another opposing slavery. Several reasons existed for this separation. Some activists did not contest the legal basis of slavery; rather, they argued that the transatlantic slave trade was brutal and murderous and should be ended. Other abolitionists supported the end of slavery (and the slave trade) entirely, promoting plans for either gradual or immediate emancipation.

Proponents of emancipation slowly gained support through the eighteenth century. In the later decades of the 1700s, the Enlightenment and the Age of Revolutions caused Europeans to reconsider and expand their ideas of individual rights and liberty. Those tumultuous decades spurred greater public support for abolitionist causes. Campaigners in Great Britain succeeded in outlawing their slave trade in 1807. Other European nations followed, but not without resistance. It took another generation (with the exception of Haiti) to begin outlawing slavery around the Atlantic. A wave of emancipation started with the British Empire in 1833 and pushed forward into the 1860s. Despite these advances, some people in the Americas continued living under slavery until the twentieth century.

Industrial Revolution Begins

Like the Neolithic Revolution that occurred 10,000 years before it, the Industrial Revolution dramatically transformed the way humans lived their lives to a degree that is hard to exaggerate. It is not difficult to define industrialization; it is simply the use of machines to make human labor more efficient and produce things much faster. As simple as this sounds, however, it brought about such sweeping changes that it virtually transformed the world, even in areas in which industrialization did not occur. The change was so basic that it could not help but affect all areas of people’s lives in every part of the globe.

See the Crash Course video on the Industrial Revolution HERE.

The Industrial Revolution began in England in the late 18th century and spread during the 19th century to Belgium, Germany, Northern France, the United States, and Japan. Almost all areas of the world felt the effects of the Industrial Revolution because it divided the world into “have” and “have not” countries, with many of the latter being controlled by the former. England’s lead in the Industrial Revolution translated into economic prowess and political power that allowed colonization of other lands, eventually building a worldwide British Empire. See the short VIDEO here.

I. Industrialization fundamentally changed how goods were produced.

A variety of factors led to the rise of industrial production:

- Geography – Europe’s location on the Atlantic, with its numerous harbors and ports, gave it access to natural resources and markets outside its borders. Industrial production occurred at such a dramatic rate—machines require massive amounts of raw materials and produce huge quantities of products—that access to foreign resources and markets was a necessity for industrial growth.

- Natural resources – Britain had large and accessible supplies of coal and iron – two of the most important raw materials used to produce the goods for the early Industrial Revolution. Also available was water power to fuel the new machines, harbors for its merchant ships, and rivers for inland transportation. Industrial growth also depended on an abundant supply of navigable rivers and canals, especially in the early stages before the railroads came.

- Social Changes – Factories require large investments of money (capital), so a thriving bourgeois class with wealth to invest was a basis for industrialization. The hereditary wealth of the aristocracy was less relevant. In fact, societies without a solid bourgeoisie had to rely on foreign investment to industrialize (think of the British investment in Ottoman and Russian industrial development). Because factories concentrate labor in small areas, urbanization was a requirement for industrialization.

- Large agricultural surpluses – The Industrial Revolution would not have been possible without a series of improvements in agriculture first in England, then spreading to other areas. Beginning in the early1700s, wealthy landowners began to enlarge their farms through the enclosure, fencing, or hedging of large blocks of land for experiments with new techniques of farming. These scientific farmers improved crop rotation methods, which carefully controlled nutrients in the soil. The larger the farms and the better the production the fewer farmers were needed. Farmers pushed out of their jobs by enclosure either became tenant farmers or they moved to cities. Better nutrition boosted England’s population, creating the first necessary component for the Industrial Revolution: labor.

- Advanced financial practices – During the previous era, Britain had already built many of the economic practices and structures necessary for economic expansion, as well as a middle class (the bourgeoisie) that had experience with trading and manufacturing goods. Banks were well established, and they provided loans for businessmen to invest in new machinery and expand their operations.

- A cooperative government – In Western Europe, particularly Britain, governments supported the interests of the business class and developing industries (think of England’s support of the East India Company). They gave legal protection for contracts and private property, a move that took some of the risk out of investing capital. Political stability also allowed for industrial growth. Britain’s political development during this period was fairly stable, with no major internal upheavals occurring, and industrialization only occurred in earnest in the United States until after the turmoil of the Civil War. Even then, the government facilitated immigration to feed to need for industrial labor in the U.S.

The transformation of labor, power, and machines In a factory, the entire production process took place under one roof. Whereas agricultural societies worked together as families around the place they lived, industrial workers had to leave home to go to work each day. In agricultural settings, a person had to learn many different things and performed a variety of tasks year-round. In factories jobs became specialized and a worker usually did the same repetitive thing all day in front of a machine. Labor no longer revolved around the rising and setting of the sun or seasons, but was ordered by the clock. Days became organized mathematically.

The first factories emerged near rivers and streams for water power, but with the discovery of the energy stored in fossil fuels such as coal and oil, location on rivers was not as important. Coal transformed power by allowing for steam engines. During the Second Industrial revolution gas engines and electricity emerged.

Industrialization Spreads

The Industrial Revolution occurred exclusively in Britain for about 50 years, but it eventually spread to other countries in Europe, the United States, Russia, and Japan. British entrepreneurs and government officials forbade the export of machinery, manufacturing techniques, and skilled workers to other countries but the technologies spread by luring British experts with lucrative offers, and even smuggling secrets into other countries. By the mid-19th century, industrialization had spread to France, Germany, Belgium, and the United States.

The earliest center of industrial production in continental Europe was Belgium, where coal, iron, textile, glass, and armaments production flourished. By 1830 French firms had employed many skilled British workers to help establish the textile industry, and railroad lines began to appear across Western Europe. Germany was a little later in developing industry, mainly because no centralized government existed there yet. After German political unification in 1871, the new empire soon rivaled England in terms of industrial production. Industrialization in the United States was delayed until the country had enough laborers and money to invest in the business. Both came from Europe, where overpopulation and political revolutions sent immigrants to the United States to seek their fortunes. The American Civil War (1861-1865) delayed further immigration until the 1870s. The United States had abundant natural resources; land, water, coal, and iron ore; and after the great wave of immigration from Europe and Asia in the late 19th century; it also had labor. During the late 1800s, industrialization spread to Russia and Japan, in both cases by government initiatives.

Technologies of the Industrial Age

The first factories emerged near rivers and streams for water power, but with the discovery of the energy stored in fossil fuels such as coal and oil, location on rivers was not as important. Coal transformed power by allowing for steam engines. During the Second Industrial revolution gas engines and electricity emerged.

The earliest transformation of the Industrial Revolution was Britain’s textile industry. In 1750 Britain already exported wool, linen, and cotton cloth, and the profits of cloth merchants were boosted by speeding up the process by which spinners and weavers made cloth. One invention led to another since none were useful if any part of the process was slower than the others. Some key inventions were:

- The flying shuttle – John Kay’s invention carried threads of yarn back and forth when the weaver pulled a handle, greatly increasing the weavers’ productivity.

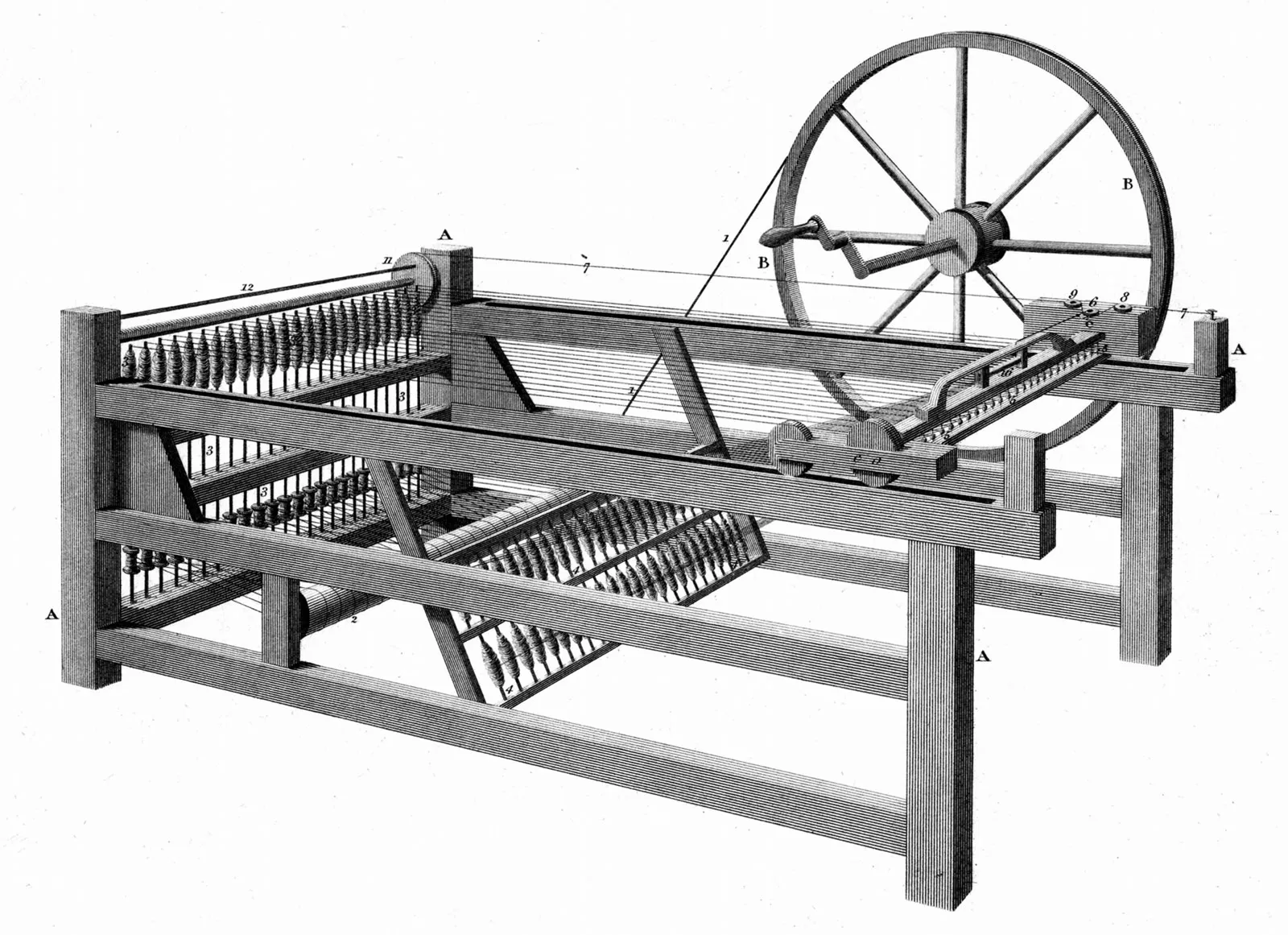

- The spinning jenny – James Hargreaves’ invention allowed one spinner to work eight threads at a time, increasing the output of spinners, and allowing them to keep up with the weavers. Hargreaves named the machine for his daughter.

- The water frame – Richard Arkwright’s invention replaced the hand-driven spinning jenny with one powered by water power, increasing spinning productivity even more.

- The spinning mule – In 1779, Samuel Crompton combined features of the spinning jenny and the water frame to produce the spinning mule. It made thread that was stronger, finer, and more consistent than that made by earlier machines. He followed this invention with the power loom that sped up the weaving process to match the new spinners.

The Impact of the Industrial Revolution

As Industrial Revolution progressed, it had a massive impact on almost every aspect of society. In many ways, it improved society and made people’s lives easier. However, it also had negative impacts in many areas as well. Here are some of the more lasting and influential effects that industrialization had on society.

During the early Industrial Revolution, working conditions were usually terrible and sometimes tragic. Most factory employees worked 10 to 14 hours a day, six days a week, with no time off. Each industry had safety hazards that led to regular accidents on the job. As the era progressed, conditions became somewhat safer. However, it would take time for workers to unionize and demand safer conditions before things improved.

Working in new industrial cities had an effect on people’s lives outside of the factories as well. Urbanization was the greatest change to an industrialized society. Cities expanded enormously as workers left their farms and migrated from rural areas to the city in search of jobs. In pre-industrial society, over 80% of people lived in rural areas. By the early 1900s, a majority of people in England and America lived in cities.

The densely packed and poorly constructed working-class tenements in cities contributed to the fast spread of disease. Neighborhoods were filthy, unplanned, and with crisscrossed muddy roads. Tenement apartments were built touching each other, leaving no room for ventilation. These often lacked toilets and sewage systems, and as a result, drinking sources were frequently contaminated with disease. Cholera, tuberculosis, typhus, typhoid, and influenza ravaged new industrial towns, especially in poor working-class neighborhoods.

For skilled workers, their quality of life decreased during the early Industrial Revolution. Machines replaced the skills that weavers were previously paid well for. However, eventually, the middle class would grow as factories expanded and allowed for managers and higher wages for workers.

Gradually, a middle class did emerge in industrial cities toward the end of the 19th century. Until then, there had been only two major classes in society: aristocrats born into their lives of wealth and privilege, and low-income working-class commoners. New urban industries eventually required more “white collar” jobs, such as business people, shopkeepers, bank clerks, insurance agents, merchants, accountants, managers, doctors, lawyers, and teachers.

Despite strong pushback from management and business owners, labor unions developed among workers. These unions used strikes, boycotts, and collective bargaining to win higher wages, shorter workdays, and other concessions that made their jobs more tolerable.

Laws were passed to end the abuses of child labor. With children in more densely packed cities, the first public school systems developed, greatly increasing the education level in society.

Women entered the workforce in textile mills and coal mines in large numbers, despite being paid less than men. Women began to organize and protest for more equality in society, most importantly for the right to vote. In the early 1900s, women finally won greater rights, including suffrage. Today, the feminist movement continues as women fight for equal pay and equal rights.